Evidence of innocence

Julie Seaman, associate dean for academic affairs and associate professor at Emory University School of Law, has served on the board of directors of the Georgia Innocence Project (GIP) since 2008, including several years as board chair. Her experiences in this role have given her a new perspective on justice for all - a perspective and passion she regularly brings into the classroom, engaging fresh new minds in the critical examination of our system of justice, year after year in Evidence class.

An obvious injustice

Julie Seaman

She continues, “He was a young, African American college student, from a middle-class family, with a private lawyer - all factors that you would typically associate with a defendant who isn’t railroaded into a false conviction. But being a black man with an all-white jury and police investigators who were fixated on him as a suspect, it’s so clear racial factors played a role.”

Seaman was so struck by Johnson’s story that she brought it into the classroom during her next Evidence course. As it turned out, a student mentioned that he had an internship at the GIP, where Johnson was an inaugural board member. Seaman invited Johnson in as a guest lecturer, which eventually led to an ongoing relationship with GIP and an appointment to the board of directors.

“My primary experience with the criminal justice system to that point was from the perspective of the victim,” Seaman explains. “Having only seen one side of the process, my attitude was that no system is perfect, but our system of justice is quite good and generally reaches fair, accurate, and just results.

“My time on the GIP board in those early days, however, crystalized for me that our criminal justice system has some pretty significant issues that are really important to address.”

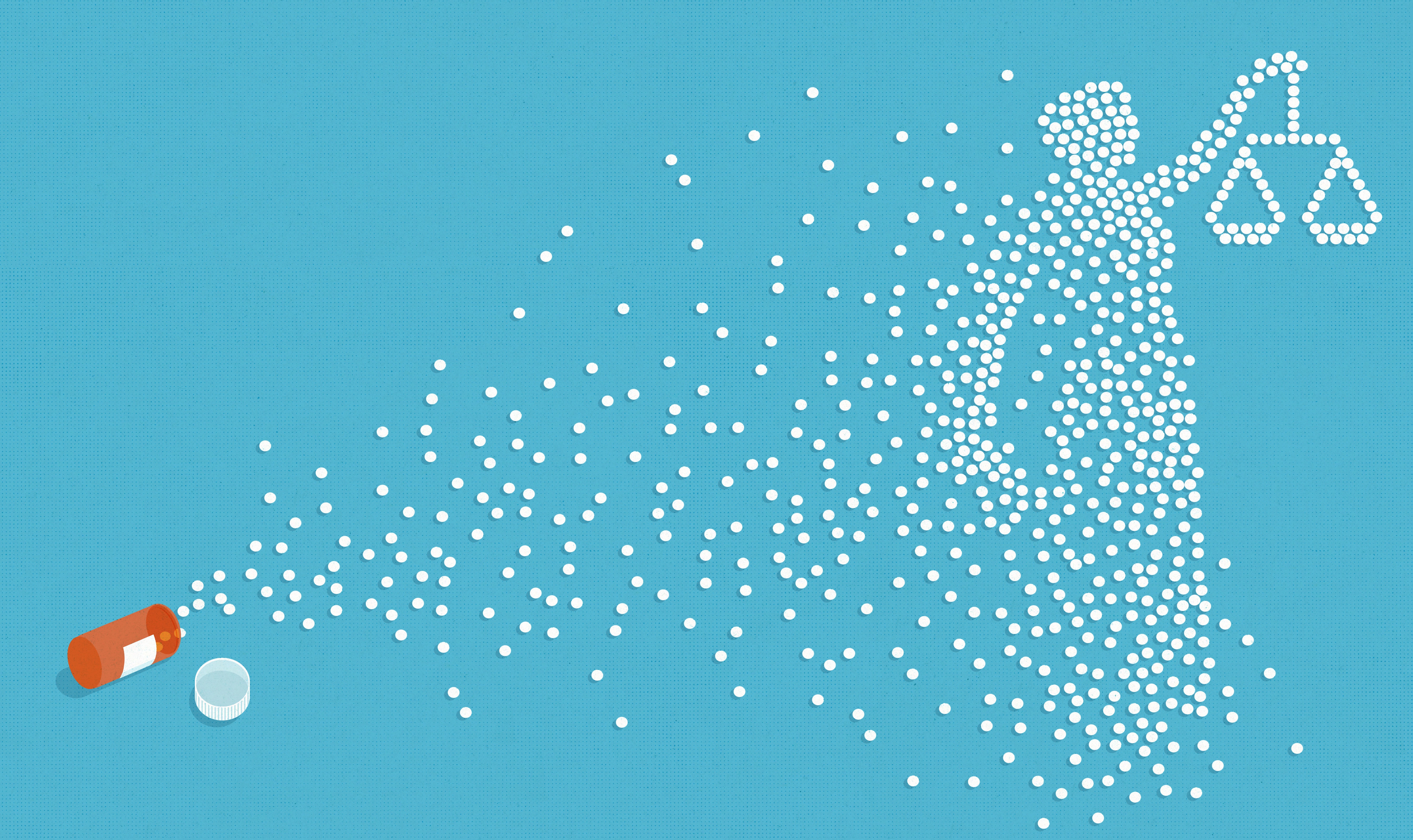

According to the Innocence Project, of the 365 DNA exonerations achieved across the US to date, 69 percent involved eyewitness misidentification, 44 percent included the misapplication of forensic science, 28 percent were the result of false confessions, and 17 percent involved informants.

In short, wrongful convictions are a complicated combination of the faults of human nature and deep systemic failures.

“The GIP and other organizations work to correct these common issues through policy work as well as individual legal representation,” Seaman says.

“The challenge is, though GIP is working on a person-by-person basis to affect change, we’ll never get to every case. Which is why I am also involved with the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, which takes a systemic, very data-driven, think-tank approach to criminal justice reform.”

Attracting attention

In the late 2000s, the Innocence Project wasn’t yet in the public consciousness. In fact, it wasn’t until the entertainment industry took an interest in some of the organization’s higher-profile cases and exonerations that the Innocence Project and its state affiliates in the Innocence Network became the topic of national conversation.

The 2012 film The Central Park Five by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon, and the 2019 Netflix Original miniseries When They See Us shocked the nation with the story of the exonerated “Central Park Five” who had been wrongfully convicted of the brutal rape and assault on a female jogger in the epony- mous New York City park.

The two-part Netflix docuseries, Making a Murderer, was filmed over the course of 13 years and follows the Wisconsin Innocence Project’s efforts to free two men they believe to be innocent of the grisly murder of a freelance photographer.

And the popular Serial and Undisclosed podcasts - which Seaman regularly infuses into the classroom - continue to spark passionate public debate with their investigation of wrongful convictions and cold cases. One particular case, which significantly raised GIP’s profile and helped the organization achieve financial stability, is the story of Georgia native Joey Watkins.

Watkins was convicted of the 2000 roadside crash and murder of a romantic rival based primarily on an incentivized informant and an overzealous police sergeant who was convinced of his guilt.

Despite ample evidence - including eyewitness accounts of Watkins’ whereabouts, extensive cell tower records proving he was actually making the 45-minute drive to his girlfriend’s house during the time of the murder, reports of a different vehicle seen driving aggressively just before the incident, and a similar unsolved shooting occurring a few miles away that coincided with dispatch taking the initial accident report -Watkins was sentenced to life plus six years.

“The media attention can be a blessing in cases like this, where there is literally nothing more we can do to advance the case from a legal perspective,” Seaman explains. “In Joey’s case, the GIP hit a roadblock until the Undisclosed podcast highlighted his situation in 2016. Over the course of the season, new evidence was uncovered, which put his case in a much better position.”

Justice for all?

Getting justice for the wrongly convicted is a lengthy process, and Seaman says that even when exculpatory evidence is revealed, it doesn’t always guarantee an exoneration.

“When GIP screens potential cases, we are looking for some possibility of biological evidence still existing,” Seaman states. “We might not know where it is or whether it still exists, but we might find it - lost for 20 years - in a box in a closet or mislabeled on the shelves in a storage room.”

Johnny Lee Gates, an African-American man with intellectual disabilities, was named by a paid police informant as the perpetrator in a gruesome murder in 1976. The state’s evidence included a coerced confession, questionable eyewitness identification, and fingerprint evidence gathered after Gates was taken to the crime scene by investigators.

The jury never heard additional evidence, including another confession and the results of blood and semen analyses which would have cleared Gates. Nor were they aware the prosecutors had ensured the case would be heard by an all-white jury.

In 2015, GIP interns located ties which were used to bind the victim. DNA testing excluded Gates, and the Muscogee County Superior Court ordered a new trial. “He’s been incarcerated for 41 years - the first 20 of those years on death row - and it is so obvious he didn’t do the crime,” says Seaman.

Seaman points out another, “outrageous example of injustice”: Sonny Bharadia’s 2003 conviction for a 2001 burglary and aggravated sexual battery. Bharadia was 250 miles away at the time of the assault and had reported that an acquaintance, Sterling Flint, had stolen his car. When investigators located Flint, he claimed the victim’s property found in his home, as well as a pair of blue-and-white batting gloves the victim had reported her attacker wearing, actually belonged to Bharadia.

Bharadia was sentenced to life without parole on the weight of Flint’s testimony against him and the victim’s eyewitness identification (though the victim was blindfolded for the duration of the assault). No DNA testing of the gloves in question was done at the time of the original trial or appeal.

A few years later, GIP took on the case and obtained approval for DNA testing - testing which revealed that the skin cells on the inside of the gloves used in the assault belonged to Flint, not Bharadia. “Under Georgia precedent, a defendant is not entitled to a new trial based on new evidence if the court finds that he could have discovered the evidence at the time of the original trial,” says Seaman.

“What is most troubling about the Georgia Supreme Court’s decision to deny our motion for a retrial is that the issue of innocence becomes irrelevant if there has been, in the court’s view, a failure of due diligence.”

The fight continues

Most scholars estimate that between two and five percent of people incarcerated in the US are factually innocent of the crimes for which they have been convicted. According to the GIP, this means that somewhere in the neigh- borhood of 88,812 innocent men and women are currently incarcerated in the U.S., 2,100 of whom serve sentences in Georgia prisons.

“It seems that if you scratch the surface of any case we’re presented, all the same kinds of problems come pouring out, and it makes you wonder how random these issues really are,” says Seaman. “If they’re happening in so many of the cases we’re looking at, what about all of the cases we’re not looking at? This is a learning process, and we still have a lot of work to do.”