One Hundred Years of Women at Emory Law

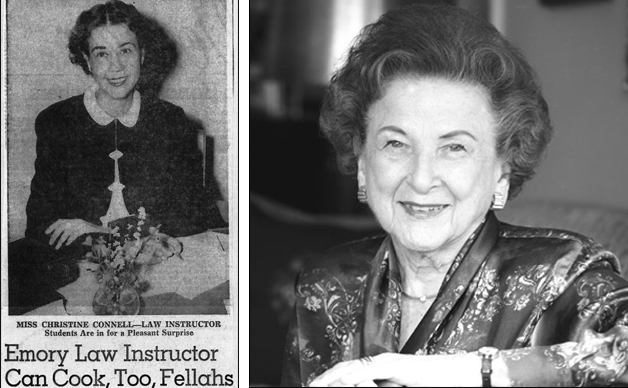

Left: Christine Connell, the first woman to teach at Emory Law joined the faculty in 1950 at the age of 33. Right: Patricia Butler 31L, a career attorney with the United States Department of Justice

Unlike a number of other prestigious law schools, Emory University School of Law admitted women from its founding. By contrast, Emory College did not admit women until 1953. By 1950, the year that Harvard Law School first admitted women as students, Emory Law had graduated 25. But the numbers remained small, as did the classes, until the late 1970s. The first class with double digits for women graduated in 1972, with 13 women earning JDs. In 1974, women made up 20 percent of the class, and by 1977, just over one-third. The class of 2000 saw the percentage of female students exceed 50 percent for the first time.

The legal profession in Georgia a century ago was inauspicious for women. In 1915, Georgia was one of only three states that did not permit women to practice law, and in fact it was forbidden by statute. Georgia’s stance received national attention, including a 1915 article in the popular women’s magazine Good Housekeeping. In an article entitled, “Your Daughter’s Career,” Good Housekeeping used the example of Georgia to warn its female readership of the obstacles awaiting the aspiring woman lawyer.

The national journal Law Notes, published in New York, also took note of Georgia’s exclusion of women in a 1916 article titled “Right of Women to Practice Law”:

Notable firsts for women at Emory Law

Out of the first ten classes to include women, three women were first honor graduates.

The first woman to serve as editor-in-chief of the Emory Law Journal was Anne S. Emanuel 75L. Emanuel is now professor of law emeritus at Georgia State and is the author of the award-winning book Elbert Parr Tuttle: Chief Jurist of the Civil Rights Revolution.

In March of 1989, Hillary Clinton delivered the seventh-annual Thrower Lecture, the first woman to do so. At the time, she was a litigation partner at a firm in Little Rock, Arkansas, and the chairperson of the ABA’s Commission on Women in the Profession. Her presentation was titled “Not for Women Only.”

Janiel Myers 18L was the first black person to serve as editor-in-chief of the Emory Law Journal. She was elected in 2017 to lead the production of volume 67.

Firsts for women in the judiciary

Orinda Evans 68L was the first woman to serve as a federal district court judge in Georgia.

Frank Hull 73L was the first woman to serve on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, appointed in 1997.

Glenda Hatchett Johnson 77L became Georgia’s first African American chief presiding judge of a state court, as well as the head of one of the largest juvenile court systems in the nation.

Justice Leah Ward Sears 80L in 1992 became the first woman to serve on the Georgia Supreme Court. She was also the first black woman to serve on a higher trial court in Georgia and the first woman to serve on the Superior Court of Fulton County. And, of course, she was the first woman chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court.

Catharina Haynes 86L became the first female Emory Law graduate appointed to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in 2008.

Three States, Arkansas, Georgia, and Virginia, however, still hold out for the old order, and just recently the Georgia Bar Association at its annual convention voted negatively, though by the small majority of two, on the proposal to admit women to practice ... But at this time of day it is too late to say that a woman shall not be permitted to pursue the vocation to which her tastes lead her and for which her studies have qualified her . . . If the practice of the law by women is not found agreeable, lucrative, or expedient, they will not seek it, and if it tends to enlarge their sphere of usefulness or to elevate and re ne the bar it ought certainly to be encouraged.

Perhaps this unfavorable attention influenced the Georgia General Assembly. In 1916, the year Emory Law enrolled its first class, the General Assembly passed what was known as the “Woman Lawyer Bill,” which permitted admission of women to the Georgia Bar. One year later, in 1917, Eléonore Raoul 20L, a notable suffragist leader and cofounder of the Equal Justice Party, began her studies at Emory.

Although during her law school years Raoul had the potential to practice law, she could not vote. In 1920, three months after she graduated, the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, guaranteeing women the right to vote. During her years at Emory, Raoul’s unstinting advocacy for voting rights included serving as grand marshal of Georgia’s first suffragist march, riding a white horse down Peachtree Street. No picture has yet emerged of that event, but some intrepid archivist may yet locate one. As an organizer of the League of Women Voters of Atlanta, Raoul headed a voter registration effort, which added 4,000 names to Atlanta’s voter rolls.

Raoul’s suffragist activities almost certainly irritated Bishop Warren Candler, chancellor of Emory from 1914 to 1922. Candler opposed coeducation as well as voting rights for women and stated his view strongly in his annual report to the Board of Trustees in 1919: “The departments of medicine and law especially should not be open to women. And, women lawyers would not promote justice in the courts.”

A few years later, Ellyne Strickland 24L became the second woman to graduate from Emory Law. She had earned a bachelor’s degree from Brenau College at the age of 16. Strickland went on to practice law in Atlanta and then in Washington, DC, as part of the Internal Revenue Service legal team that prosecuted Al Capone for tax evasion. At the time of her retirement on December 31, 1959, she had completed approximately 20 years in the Appeals Division of the New York Office of the Internal Revenue Service, Office of the Chief Counsel. Strickland was admitted to practice before the Bar of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Nana (Chatham) Wolfe 28L was the third woman to attend Emory. e 24-year-old graduated first in a class of 12, making her the first woman to achieve the status of first honor graduate. Wolfe was a founding member of the Georgia Association of Women Lawyers and served as an officer of that organization in 1930. The class of 1931 included one of Emory Law’s most accomplished early graduates. Patricia Butler 31L was a career attorney with the United States Department of Justice, serving in various capacities under 16 different attorneys general in her 40-year career. Among notable firsts for Emory women, she was admitted to practice before the US Supreme Court in 1939; she was also a founding editor of the Federal Register and was one of the architects of modern administrative law.

On the faculty side, Christine Connell, whose title was “law instructor,” was the first woman to teach at Emory Law, joining the faculty in 1950 at the age of 33. e Atlanta Journal took note, introducing her with the headline, “Emory Law Instructor Can Cook, Too, Fellahs.” Under a large picture of Connell, the article continues:

Law students at Emory University are in for a distinct shock. And a very pleasant one. Upon entering a class in legal bibliography, they will find themselves face to face with one of the less stern aspects of the law. Namely their instructor, Christine Connell.

Prior to coming to Emory, Connell had been law librarian at the University of Alabama and taught legal bibliography. (which the Atlanta Journal explained, “concerns which law books to use and how to find what you want in them.”)

Lucy Heinreitze 66L — later to become Lucy McGough Bowers —was the first tenured woman, first Candler Professor for the law school, and first female Candler Professor at Emory University. She served on the faculty from 1970 to 1983. Bowers is one of Emory Law’s best-known graduates in law teaching. She taught at LSU for more than 25 years after leaving Emory as the Vinson & Elkins Professor of Law. She served as the eighth dean and president of Appalachian School of Law.

In a 1970 article in the Atlanta Journal, Bowers noted: “A great many law schools in the country still have no women on their faculties. Emory is an amazingly progressive school, and that is one reason I feel so responsible — that they have overcome their reservations about women professors.”

Thee Legal Association of Women Students (LAWS) was established in the 1970s. At the beginning of the decade, women represented only 9 percent of the total; by the end their share had more than quadrupled to 39 percent. The celebrated LAWS “Pub Night” charity auction, featuring donations from faculty members, began in the 1970s and continues to the present day. Creative faculty donations are too numerous to detail, but certainly a favorite was an aerobics class led by Professor William Ferguson. LAWS has also sponsored the annual 5K Race Judicata for nearly three decades.

Numerous Emory Law women have achieved success in law, business, education, and politics — too many to report in this short space. With this firm foundation, Emory Law maintains its commitment to the support of all genders.

Research assistance was provided by Vanessa King and Terry Gordon.