WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

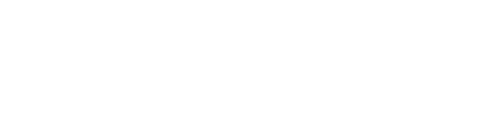

The 19th Amendment

and

Eléonore Raoul’s Role in the Struggle

MORE THAN A CENTURY AGO,

ATLANTA’S TRAFFIC WAS ALREADY

MAKING HEADLINES —

FOR OBSTRUCTING THE CITY’S FIRST

WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE PARADE.

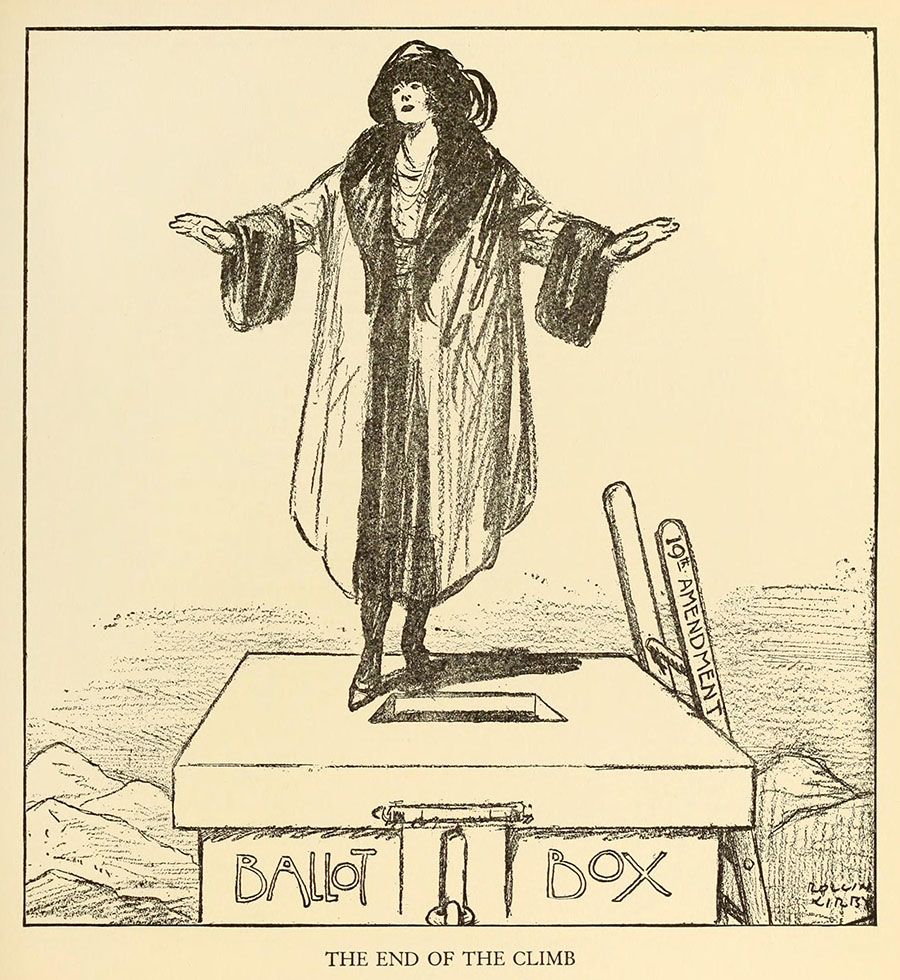

“Georgia suffragists were indignant over difficulties encountered downtown yesterday,” the Atlanta Constitution wrote on November 17,1915, “when their procession moved through a maze of traffic suddenly loosened in their route which made progress exceedingly slow and cumbersome.”

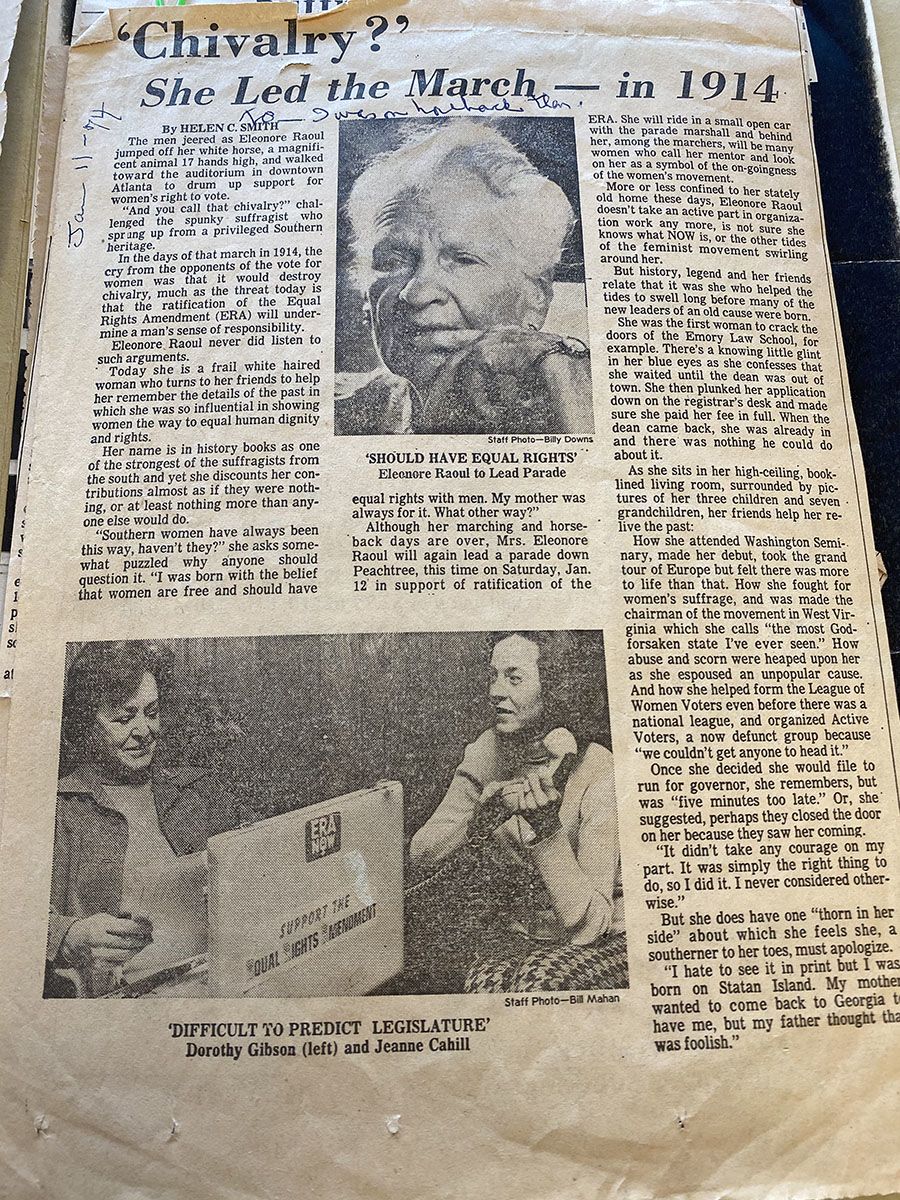

Led by Eléonore Raoul 1920L 1979H on a white horse, the parade gathered between 500 and 1,000 marchers who were undaunted by the traffic, the paper reported. The obstacles in the women’s path were a fitting symbol for their fight for the right to vote in Georgia: four years later, it would become the first state to reject the 19th Amendment.

The beginnings of the women’s suffrage movement in Georgia were modest. In 1890, Helen Augusta Howard and ten other women in Columbus, Georgia, formed the Georgia Women’s Suffrage Association. In the group’s constitution and bylaws, it invited “all persons of either sex, who admit the justice of women’s demand to be raised about [sic] the political level of minors, lunatics, felons, and traitors, with whom they. . . [were] classed by the Constitution of Georgia.” The state’s “one unpardonable crime,” the association argued, was being a woman; minors would gain the right to vote with age, and even criminals could have their full rights restored with a pardon.

Without Howard’s influence, Georgia would likely have taken much longer to gain momentum in the fight for women’s right to vote. In 1895, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) planned to hold its first convention outside of Washington, DC, a location originally chosen for the possibility of influencing Congress with its presence in the city. However, Howard convinced delegates to vote for Atlanta, arguing, “The Georgia papers and the far Southern papers still insist that women do not want the ballot. Until you hold a convention in the South and prove to them that this is not so, they will keep on saying it is.” Howard suggested that Atlanta’s Grand Opera House would be “packed from ceiling to pit” and noted, “While a great many of them would come to laugh, many of them would go away with NAWSA membership tickets in their pockets.”

Ultimately, Howard was correct: on January 31, 1895, the Atlanta convention attracted significant media attention and 2,000 attendees from across the country, and inspired the formation of a NAWSA-affiliated organization in the city.

Eléonore Raoul: A leader in the cause

At only age eight, Eléonore Raoul was not in attendance — but she soon became a prominent organizer, as well as the first woman to graduate from Emory University in 1920.

“You might say I was brought up with the suffrage movement,” Raoul said in a 1977 interview with the Emory Wheel. “Mother was very much for women’s rights. It seemed a natural thing to do.”

By 1914, there were three state suffrage organizations: the first Georgia Women’s Suffrage Association, which counted more than 1,000 members, the Georgia Woman Suffrage League, with 500 members primarily located in Atlanta, and the Equal Suffrage Party, which Eléonore’s mother, Mary Millen Raoul, and her sister, Mary Raoul, founded with Emily C. McDougald in the hopes of creating an organization that would more aggressively work for suffrage. By 1915, the Equal Suffrage Party had a membership of nearly 2,000 women. None of these organizations admitted women of color in Georgia, and the efforts of women like Lugenia Burns Hope, who advocated for suffrage through her work with the Atlanta community organization Neighborhood Union, or Mary A. McCurdy, the African American suffragist editor of Woman’s World in Rome, Georgia, have been either rarely acknowledged or totally neglected in published histories of the movement until recently.

In the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia, Raoul served as organizer and press agent and chair of the Suffrage Parade Committee. She also served as organizer and later chair of the Fulton and DeKalb Counties Branch until her resignation in March 1916. During Eléonore’s involvement, the state organization published a number of materials, including “Why Georgia Women Should Vote” and a leaflet titled “Chief Justice Clark, of North Carolina, on White Supremacy.”

Women supported the movement for different reasons. Often, they were motivated by the desire for a greater legislative focus on issues like child labor laws, temperance, and public safety. Among common reasons for suffrage detailed in the Equal Suffrage Party’s pamphlet were the unfairness of women’s taxation without representation, the idea that women are not identical with men and must represent their special interests by voting, and the sentiment that as the mothers of citizens, women have the “greatest possible stake in the government and deserve the greatest possible honor and power.” In an interview with the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine later in her life, Eléonore said, “I went into suffrage because I thought it was just and that it was the most effective way for women to uphold their chief interests — the home and children. Women’s interests must be represented in government.”

Particularly in the South, suffragists frequently argued that a woman’s right to vote was expected to strengthen white supremacy in the region. In its leaflet, the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia made this argument directly, quoting Chief Justice Walter Clark of the Supreme Court of North Carolina. According to the leaflet, Clark was asked if white supremacy was endangered by the prospect of giving Black women the right to vote. Instead, Clark answered that equal suffrage would “save the day” for white supremacy, stating, “the 260,000 votes of the white women of the State will be one solid obstacle to any measure that would impair either for them or their children the continuance of white supremacy.”

In her letter of resignation from the Equal Suffrage Party, it’s evident that Raoul had a distinct vision for the suffrage movement in Georgia and felt at odds with the state president, then Emily C. McDougald. She said, “Our President has taken our desire to consult with her on the best method of attaining the desired end of unification of suffrage societies in Georgia as a personal matter. My belief in the necessity for this unification is so strong, I am so positive that without it an effective fight for the ballot can not [sic] be made that I deem it unwise for the cause that I longer remain in office when I am at variance with the president on so vital a point.” Raoul specifically notes her “failure to work in harmony with the state president” and her strong feelings that she could not “conscientiously carry out” policies with which she disagreed.

In two letters Raoul received in August 1916, it appears her resignation may have caused her later problems. “When I invited you to make the report of the work in Atlanta, I thought it wise to write to the three presidents in Atlanta,” Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association writes. “I thought it would be very nice to give you the opportunity to make the report and thus, to introduce you to the Convention. One of them objected. . . . Since she does object, I think it will be better that you do not do it.” Catt wrote a second time to ask Raoul to refrain from all speaking at that time, but also suggested that Raoul would be offered the opportunity to develop that ability in the future.

“Around about 1913 and 14, the world was all aflame because women were demanding the right of suffrage,” Mary Raoul Millis wrote in her memoir The Family Raoul. She notably did not include her family’s involvement with the Equal Suffrage Party of Georgia but did describe her sister’s other suffrage work. After her resignation, Raoul traveled to support the suffrage campaign, spending time as a paid worker in New Jersey, organizing in West Virginia, and at the national NAWSA office in New York. Mary noted Raoul always “attain[ed] success in what she chose to do,” and wrote that although she was placed in West Virginia’s most difficult areas, the only two counties in the state that voted for suffrage in the next election were Eléonore’s responsibility.

Raoul frequently corresponded with her mother from the campaign trail, and they were demonstrably close. Mary observed that their mother was “always an ardent proponent of the rights of women” who “gave both money and time to the campaign in Georgia and Atlanta, finding great happiness in the companionship of Raoul in this most vital work.” Raoul frequently corresponded with her mother about her work with NAWSA. In a letter dated September 25, 1916, she related praise from Dr. Effie Jones, the national field secretary, and wrote, “she said she had written Mrs. [Carrie Chapman] Catt that I had certainly handled a very difficult situation here well. The difficult situation was trouble between my new campaign committee and a few of the older suffragists. It is all straightened out now. I was delighted of course that she had written that to Mrs. Catt but it never occurred to me that she would. Now I suppose you will think my head is turned.”

Raoul also shared ideas on how to reach more supporters as she traveled back to Georgia, while also demonstrating her thriftiness: “I am going to ask the National if they will send a speaker with me and pay half of the traveling expenses to Georgia if I take my car back after the election. We will hold meetings all of the way down and it would be an excellent add for suffrage.” In December 1916, Raoul appeared confident in the skills and experience she’d gathered, and wrote her mother from New York, “We will have quite a good crop of Georgia workers at this rate and some good material ready for Ga. when she is ready. The more I see of things the better position I think I have.” Other organizers thought highly of her as well; six months later, she received a letter dated June 16, 1917, from the National Women’s Party that asked her to visit Washington, DC, to help with their work, which at the time included the famous picketing of the White House.

In her letters, Raoul is frank, independent, and focused on her future. She often discussed her salary as an organizer with her sister Rosine (“I am going to write her that I am absolutely unwilling to work for a salary of less than one hundred a month and expenses. That is what several of the other workers are getting”) and directly made her case for what she believed was fair pay with NAWSA. She shared her successes with Rosine, noting many compliments on her work from other established suffragists. However, she also frequently expressed self-doubt, being particularly concerned about her public speaking ability despite frequently reporting her speeches were well received; her papers contain a number of jokes, anecdotes, facts, and verse she presumably found successful.

Driven to public service

Raoul was also driven to public service. On August 6, 1916, she weighed her options in a letter to Rosine, and said, “The only thing I can think of taking up at home is recreation work with the idea that eventually I can work up something big — public baths etc. and even something for negroes which is needed very badly.” She mentions the possibility of law school over continuing suffrage work, which would require living away from home for several years: “Then I have even thought of my lawyer idea again. I think there will be a continually growing demand for women lawyers and it occurred to me that I might just settle down to that and start by taking the Atlanta law course.”

As the story goes, Raoul enrolled at what was then the Lamar School of Law in 1917 while Chancellor Warren Candler was away and unable to block her entry, given his strong objections to graduate education for women. With her experience fighting for women’s equality and her independent nature, it’s no surprise she chose to enroll one year after Georgia granted women the right to practice law. Raoul became the first woman to graduate from Emory University in 1920, three months before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. After practicing law for one year, Raoul chose to focus on her work with the League of Women Voters. She told the Emory Wheel, “I didn’t appeal a case I ought to have appealed and I said to myself, ‘I’ve got to make a decision.’ There were plenty of good lawyers around, but no one to do the kind of work I was interested in.”

While in law school, Raoul was still active in the Georgia suffrage movement. In 1918, Alice Paul, national chair of the Women’s Party, wrote requesting she accept the role of chair in the branch in Georgia, which Paul described as “nonexistent.”

Instead, in 1919, Raoul was the chair of the Central Committee of Women Citizens, where she led a massive voter registration campaign. That year, women would be allowed to vote in Atlanta’s white Democratic primary. On August 3, 1919, the Atlanta Journal reported on the campaign’s progress toward its goal of registering 5,000 women, and Raoul felt positive about their progress, stating, “You must remember that this trial at citizenship came upon us rather suddenly, and we have had a comparatively short time to get the message to the average woman.” Ultimately, 3,784 women registered, the Constitution reported, with the promise that their $1 poll tax would be collected and spent on the public project they chose. After the election, Eléonore’s legal training background became even more valuable when the money was not turned over to the women’s committee as promised; legal action was eventually settled in 1930 in the women’s favor.

In Georgia, anti-suffrage groups outnumbered activists. They warned that giving women the vote would cause civil unrest, violence, and the loss of traditional gender roles. It’s no surprise that the state was the first to vehemently reject the 19th Amendment; in fact, ratification resolutions were introduced to the legislature solely for the opportunity to defeat them. “If you pass the Nineteenth Amendment you ratify the 15th and any southerner [so doing]. . . is a traitor to his section,” said Representative J. B. Jackson. Ultimately, even with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, women in Georgia were still unable to vote in a national election until 1922: Georgia law required that voters register six months before an election, and the state congress refused to waive this rule with an Enabling Act. Additionally, Georgia laws created to inhibit the votes of Black men would also prevent women of color from benefiting from women’s suffrage in 1920.

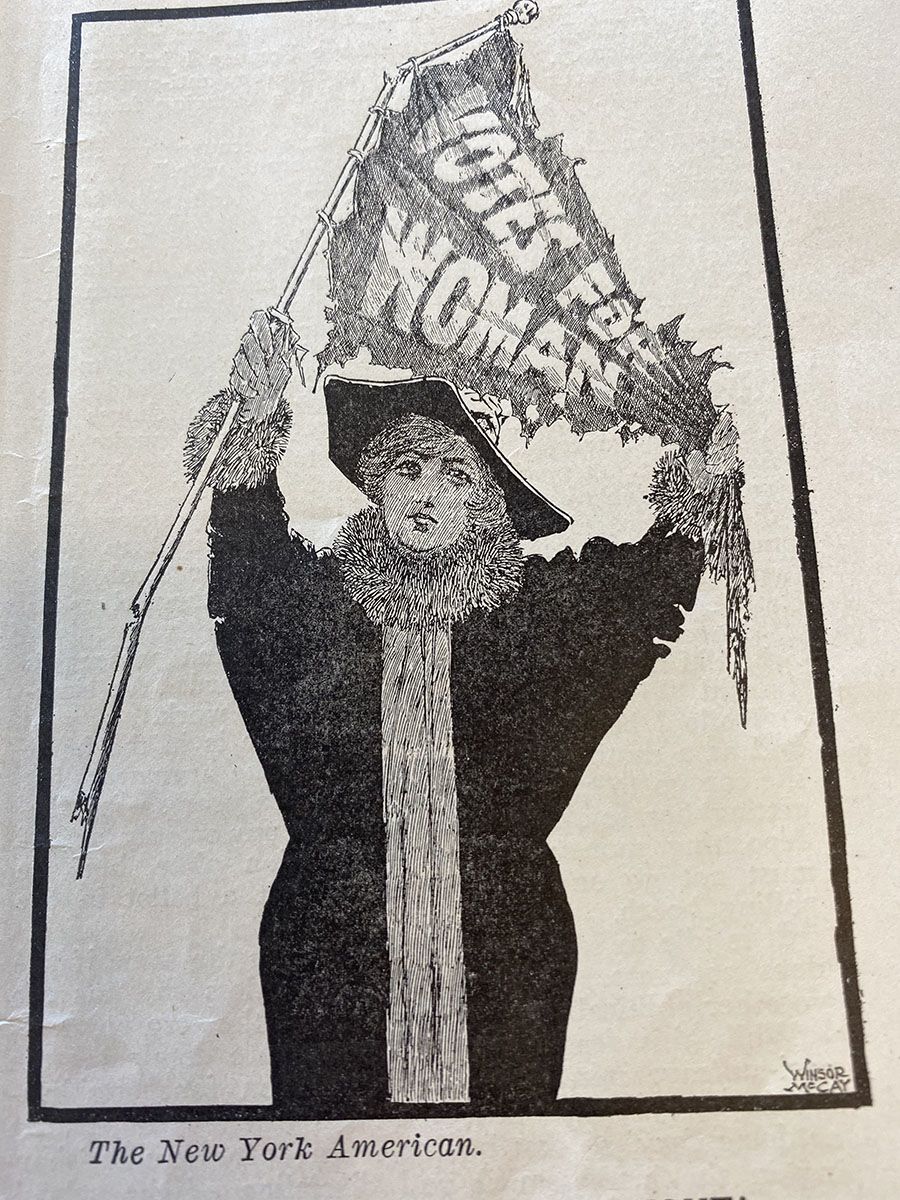

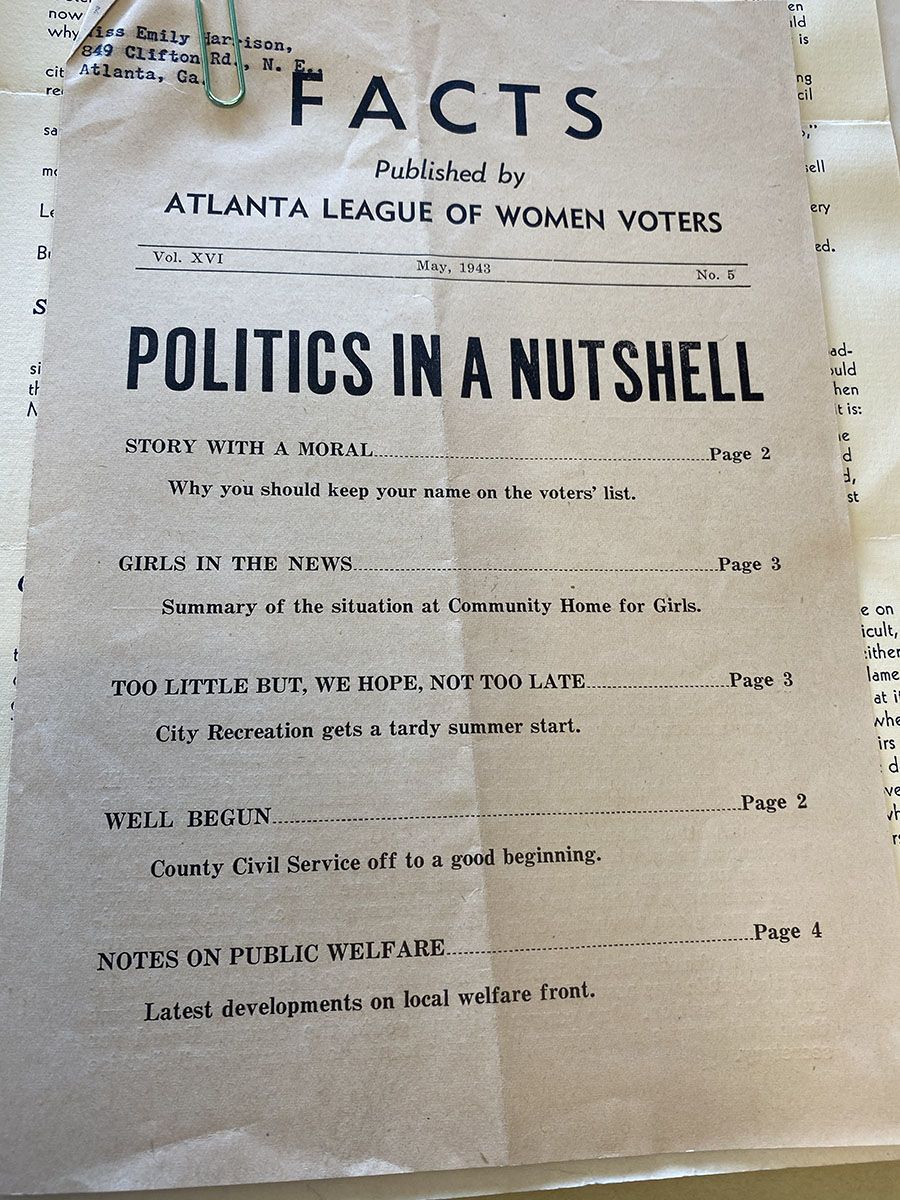

With the right to vote came the need for voter education. Raoul’s dedication to this effort resulted in the founding of the Atlanta chapter of the League of Women Voters in 1921, an organization she led as president and remained involved with throughout her life. In an April 1922 letter to registered voters signed by Raoul, the Atlanta League said, “The Committee believes that the people should have what they want but that before they vote they should be willing to give enough attention to all sides of the question to be sure that they want that for which they vote.”

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Courtesy of Raoul Family Papers, 1865-1985, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Deborah Dinner, Associate Professor of Law, Emory University School of Law

Deborah Dinner, Associate Professor of Law, Emory University School of Law

Looking forward

Traditionally, the women’s suffrage movement is considered the start of first-wave feminism in the US, marked formally at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. As of July 1, 2020, more than 150 years later, Georgia women make up a larger percentage of active voters than men. They voted in greater numbers than men in the November 2014, 2016, and 2018 elections. However, women are still underrepresented in elected office in Georgia and across the nation, and they experience many other socioeconomic disparities.

“The feminist movement made great strides toward formal equality under law — same treatment for similarly situated individuals,” said Deborah Dinner, associate professor of law at Emory. Dinner is a legal historian whose scholarship examines the interaction between social movements, political culture, and legal change. She continued, “They also fought hard for a welfare state that would support women’s gendered experiences — as pregnant persons, primary caregivers, divorced homemakers, mothers, and daughters. They advocated universal childcare, protective labor laws, the expansion of disability insurance, paid family leave, and just labor conditions for domestic workers and home health care workers.”

But, she noted, there is still work to be done. “Social and market conservatives thwarted these more ambitious goals. This is the agenda left for feminists today. We need to continue to combat gender stereotyping, including that which inhibits the freedom of LGBTQ people, while also fighting for state support for care work, paid and unpaid.”

On July 25, 1919, the Atlanta Constitution quoted Senator Dorris (presumed W. H. Dorris, but unclear in the texts) as he lamented Georgia’s rejection and hoped, “Some day some future legislature sitting in the same seats now occupied by us will see the light, the great light of the rising suffrage sun, and that day they will remove from the name of the state of Georgia that blot which we are now imposing on it. May that day come soon.”

Although the state eventually ratified the amendment, it wasn’t soon, and arguably did not restore the state’s reputation: In 1970, Georgia made a symbolic gesture by ratifying the 19th Amendment rather than supporting the Equal Rights Amendment. Today, the state continues to struggle with accusations of voter suppression, and the work to ensure equal voting rights continues across America. When asked about the next legal step towards guaranteeing voting rights to all Americans, Dinner commented, “In his eulogy for John Lewis, Barack Obama called for a series of reforms that would secure voting rights. These included: ending partisan gerrymandering, restoring the full Voting Rights Act in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, guaranteeing the franchise to felons, making Election Day a federal holiday, extending the franchise to citizens living in Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico, expanding early voting, and protecting the voting rights of students. We would make great strides toward a more equal democracy if we heeded Obama’s impassioned call.”

In an undated draft of a speech found in her papers, Raoul made a similar call to action. She asked, “Shall we align ourselves with the ones who talked against the Constitution and harped on state sovereignty, or shall we be on the side of the Washingtons, Jeffersons, and Hamiltons and be willing to give up national sovereignty [sic] if necessary for the progress of the world to a fuller democracy?”

Research assistance provided by: Atlanta History Center, Emory University Rose Library, Gary Hauk, and League of Women Voters Atlanta