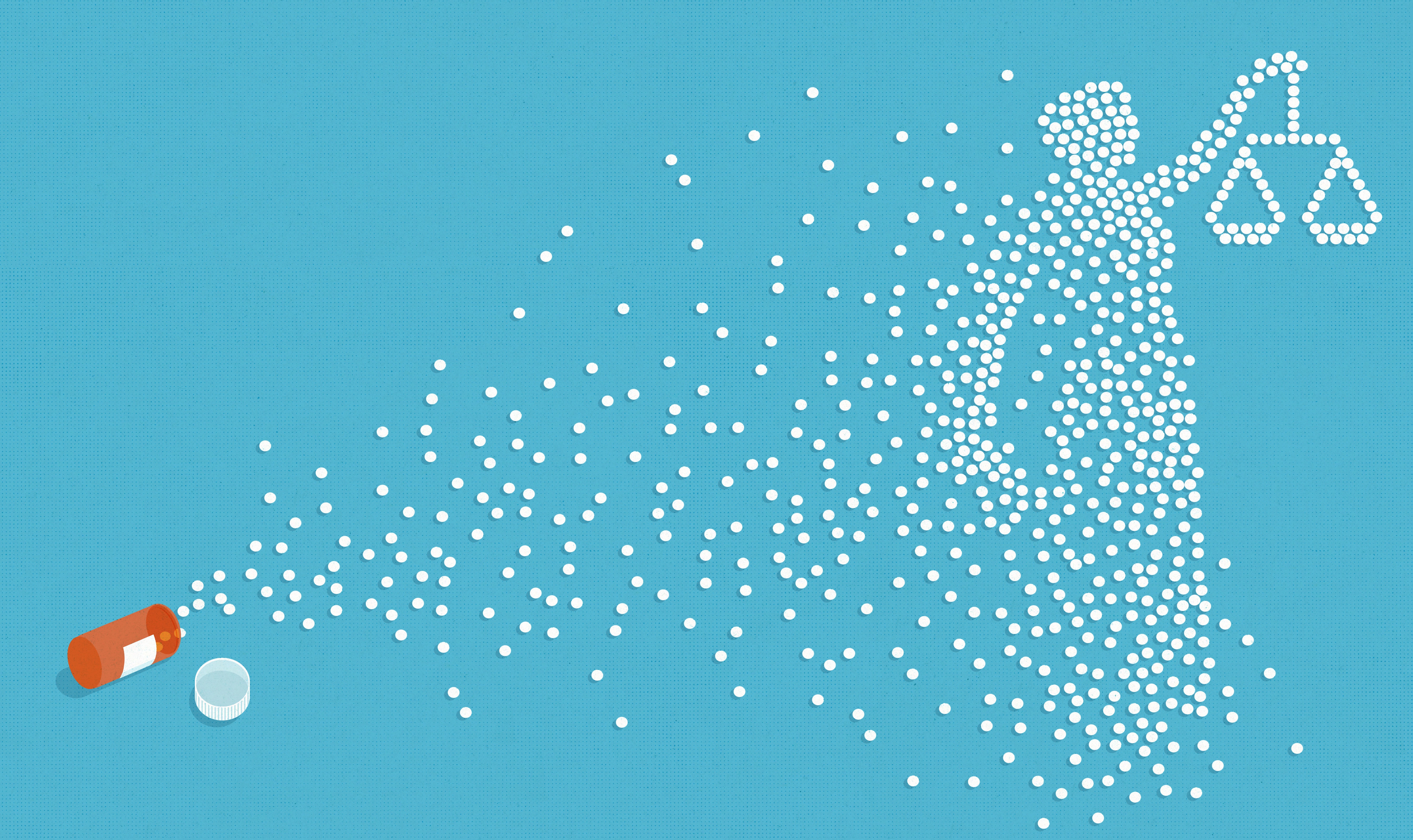

A nation in crisis

What we are trying to do is use a class procedure in a novel way - to assist in global settlement negotiations, rather than to litigate each claim. - Paul Geller 93L

Nearly 30 years ago, on the heels of the “war” on illicit drugs, another crisis began to grip the nation. This time, instead of illegal drugs pouring into communities, wave after wave of prescription opioid addictions and deaths ripped through the country, leaving a trail of financial and physical devastation in its wake. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 700,000 opioid overdose deaths were recorded between 1999 and 2017.

How could a legitimate medication, touted by the pharmaceutical industry as a safe and low-addiction-risk means for alleviating patients’ suffering also unleash a public health catastrophe of this magnitude? And, more importantly, as the country grapples with ongoing opioid abuse, who must be held accountable for the financial cost and the loss of life?

Pending legal actions allege the pharmaceutical industry employed aggressive marketing and intentional dissemination of misinformation on the highly addictive nature of these medications. “We’ve seen a collective effort on the part of the industry to change the way the American medical community, and the American public, viewed the use of opioids,” says Mark Chalos 98L, managing partner of Lieff Cabraser’s Nashville office and member of Emory’s Select Committee on Class Actions. “We allege that their intention was to create a perception that using opioids was safe, without very much risk of addiction.”

A litigation model emerges

In Oklahoma earlier this year, the first public opioid trial in which the state sued global megacorporation Johnson & Johnson using a “public nuisance” strategy, alleging the company is responsible for fueling one of the worst drug epidemics in U.S. history. On August 26, a landmark decision was issued. In a move expected to shape future litigation, Cleveland County District Judge, Thad Balkman, ordered the company to pay $572 million for its part in the state’s opioid epidemic.

Elsewhere, courts have so far only heard litigation on behalf of states, local jurisdictions, and groups, but with the sheer volume of cases pending, more than 1,500 federal complaints were bundled together last year under one multidistrict litigation (MDL), presided over by US District Court Judge Dan Polster. This fall, the MDL will have its first trial, expected to become the bellwether in opioid litigation.

Jaime Dodge, director of Emory University School of Law’s Institute for Complex Litigation and Mass Claims, says the institute is following the Ohio MDL closely.

“The MDL is being entrusted with the most difficult problems of our time,” Dodge says. “For many, there’s a recognition that in some of these cases it’s not just a dollar or cents issue; it’s about fixing ongoing societal problems - and that will require innovation and novel solutions.

“But for others, there is a concern that the enormity of the problem will result in accept- ing a rough justice that short-circuits due process - and sets a precedent for that to occur in future, less novel cases. The Institute has been at the forefront of the process, helping judges and counsel develop the right innovations to best effectuate justice for all parties. This work has become crucial as these massive cases become more and more frequent, with MDLs now comprising more than half the federal civil docket.”

Paul Geller 93L, managing partner of Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd, and a member of the Institute’s board of directors, is representing a number of plaintiffs in the Ohio case. Geller is part of a team that is taking the unconventional approach of filing a motion for certification of a negotiation class, rather than a traditional litigation or settlement class.

If approved, the motion would gather the thousands of counties and cities that have been impacted by the crisis into a single negotiating class for the “sole purpose of negotiating and potentially settling with defendants conducting nationwide opioids manufacturing, sales, or distribution.”

“Political subdivisions like counties and cit- ies have filed lawsuits both in state and federal court,” Geller explains. “What we are trying to do is use a class procedure in a novel way - to assist in global settlement negotiations, rather than to litigate each claim. Ultimately, it will take collaboration and coordination among the various plaintiff groups to ‘land the plane.’”

Attorneys for the plaintiffs are applying a number of legal theories to underpin the prosecution.

“Opioid MDL cases are being tried primarily under the federal racketeering statute, meaning the prosecution alleges that these manufacturers and distributors engaged in a long, wide-ranging scheme to collectively defraud the American public and the medical community,” Chalos says. “Opioids are part of a closed system, like all controlled substances, and federal and state law require these companies to know where their drugs are at all times.”

Chalos says dumping tens of billions of oxycodone and hydrocodone pills into American communities over a six-year period hardly counts as ethically responsible. “The Washington Post recently reported that the DEA’s ARCOS database showed that 76 billion opioid pills were manufactured and distributed throughout the US between 2006 and 2012. That’s over 240 pills for every man, woman, and child. This crisis is not the fault of the American public.”

Geller concurs, “Consumer protection laws, RICO and public nuisance laws are on the books to protect against companies putting the public at risk while they profit off of the sale of potentially dangerous products. If companies use adequate warnings and don’t violate the law in the manner in which they market and sell, then they have nothing to worry about. But that isn’t the case here.”

The path forward

Both Geller and Chalos represent plaintiffs in the Ohio MDL. Although neither can divulge specifics on an active case, both say enough evidence already in the public record paints a dim view of the conduct of manufacturers, distributors, and other actors within the industry.

“In a very short period of time, opioids went from being rarely used - and only for chronic illnesses such as terminal cancer and palliative care at the end of life - to a patient receiving a 90-day prescription for OxyContin after something as simple as a tooth extraction,” Chalos says. “At the same time, we saw distributors making billions of dollars on dumping massive amounts of opioids into communities where there weren’t enough people to justify that volume. That was a dramatic sea change.”

The hope is, a favorable ruling in the Ohio MDL will go a long way toward not only recovering billions of dollars spent fighting opioid addiction in states and municipalities across the US, but also affect systemic change.

“This is one of those rare instances where large-scale litigation may be the vehicle that achieves what other efforts have been unable to do,” Geller explains. “We are fighting not only to reimburse state and local governments who have taken the brunt of the financial burden of this deadly epidemic, but more importantly, we are fighting for funds to increase treatment beds and recovery programs, to educate the public and re-educate health care providers, to get Naloxone (narcan) into the hands of all first responders, and to ban the promotion and lobbying of opioids, among many other goals.”

The Herculean efforts to stem the tide of addiction and the opioid-related death toll is also gaining traction outside of the courtroom. On October 24, 2018, President Trump signed into law the bipartisan Substance Use Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (support) Act.

The support Act expands the industry’s reporting obligations under the federal Physician Payment Sunshine Act as well as includes multiple provisions to address the opioid abuse epidemic nationwide.

Assistant Deputy Attorney General for the District of Columbia Jimmy Rock 03L 03T, says resolution will require a collaborative effort. “This is an ‘all-hands-on-deck’ government response. The state and local governments are on the front lines of this crisis, but the federal government is certainly also going to continue to have a role in stemming the tide.”

Prescribing in good faith

What about the medical community? Are doctors complicit in this epidemic, or were they acting in good faith to meet a legitimate need for pain relief in their patients? “There’s a whole generation of doctors who were told from the time they were in medical school, when your patient is in pain, if you’re a good doctor, you give them a pill,” says Chalos. “Of course, there are bad actors, doctors who were running pill mills, but the vast majority of them were relying on the manufacturers to give them accurate information.”

Geller says that responsible pain management is the key. “There is no question that there are legitimate uses for pain medicine - and for the most part, when good, honorable, and properly educated doctors are treating patients who have legitimate needs, and when the amount and dosage is carefully monitored, you don’t see the problems that we’re dealing with in the opioid litigation.”

The advent of legal and legislative action, though still in its infancy, is producing another sea change in medical care. “There’s been a gradual shift back in the way doctors are perceiving opioids and laws have been enacted in some states that encourage doctors to prescribe a shorter course of these drugs,” Chalos reports. “We’re also seeing insurance companies looking more carefully at the length of a prescription and denying coverage when deemed necessary, such as for pregnant women, in an effort to eliminate cases of neonatal abstinence syndrome.”

Unintended consequences

There’s a lot riding on the upcoming litigation - and not just for those municipalities and other groups seeking damages. Perhaps one of the most difficult unintended consequences to relieve is the harm done to the end users - the patients - and their families.

“The patient is a very important part of the picture here,” Chalos explains. “Everybody agrees that patients who have a legitimate medical need for opioids or any other pain relief, should have access to them. What we want to happen here is for doctors to be given the full picture, including accurate information about these drugs, so that they can prescribe and monitor responsibly. Opioids are highly addictive, and that must be factored in.”

Dodge agrees, “There are people who really need these drugs, so you can’t shut down the chain of commerce entirely. That makes it very difficult to think about how to craft injunctive relief so you have a way to get justice for the plaintiffs without unintentionally harming others.”

Solving the opioid abuse crisis will take the proverbial village because, as Chalos says, unlike the cocaine epidemic, the opioid abuse epidemic is much more insidious. “I think the major difference between the opioid epidemic and the ‘war on drugs’ is that what we’re experiencing with opioids has its roots in the corporate board rooms of billion-dollar corporations. As long as a pharmaceutical company is making billions or tens of billions on opioids, there’s not much incentive to investigate alternatives. Our goal is that, ultimately, the MDL litigation will have a dramatic impact on the industry’s conduct and will make a change in our communities for the better.”