Big tech, government, and civil liberties

Privacy in the technology age

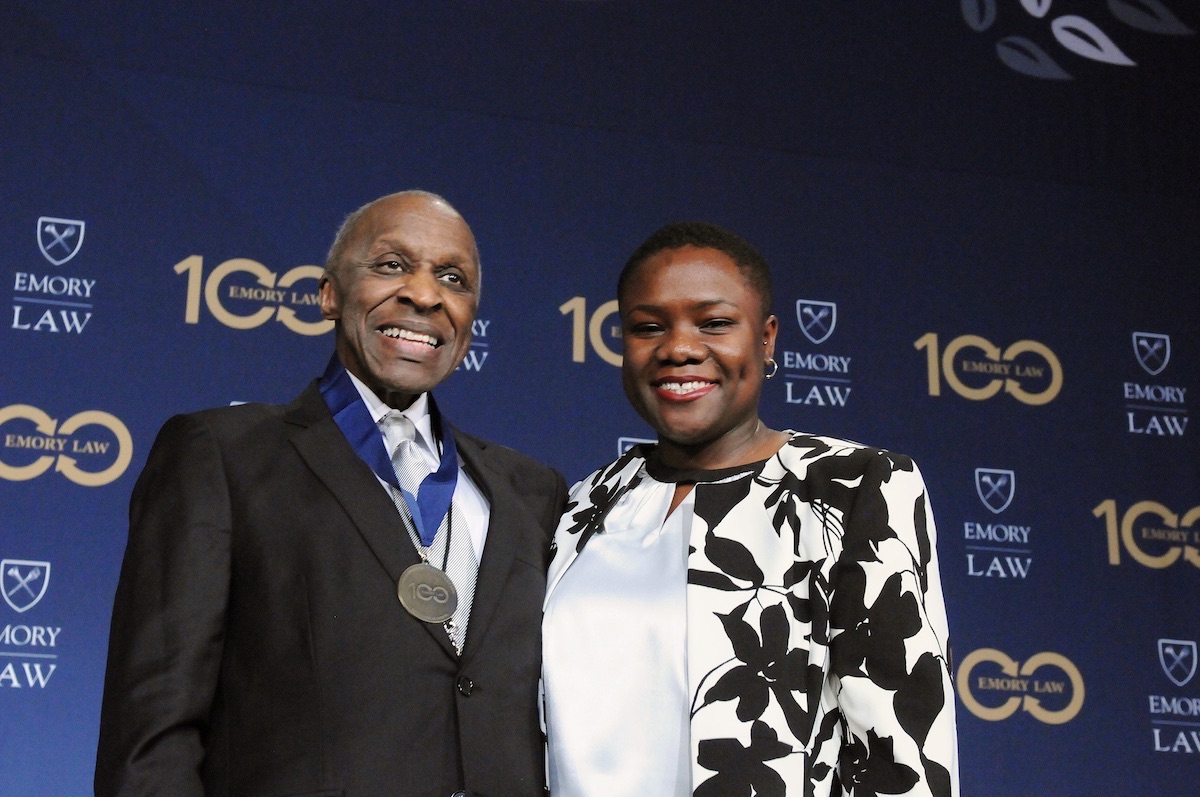

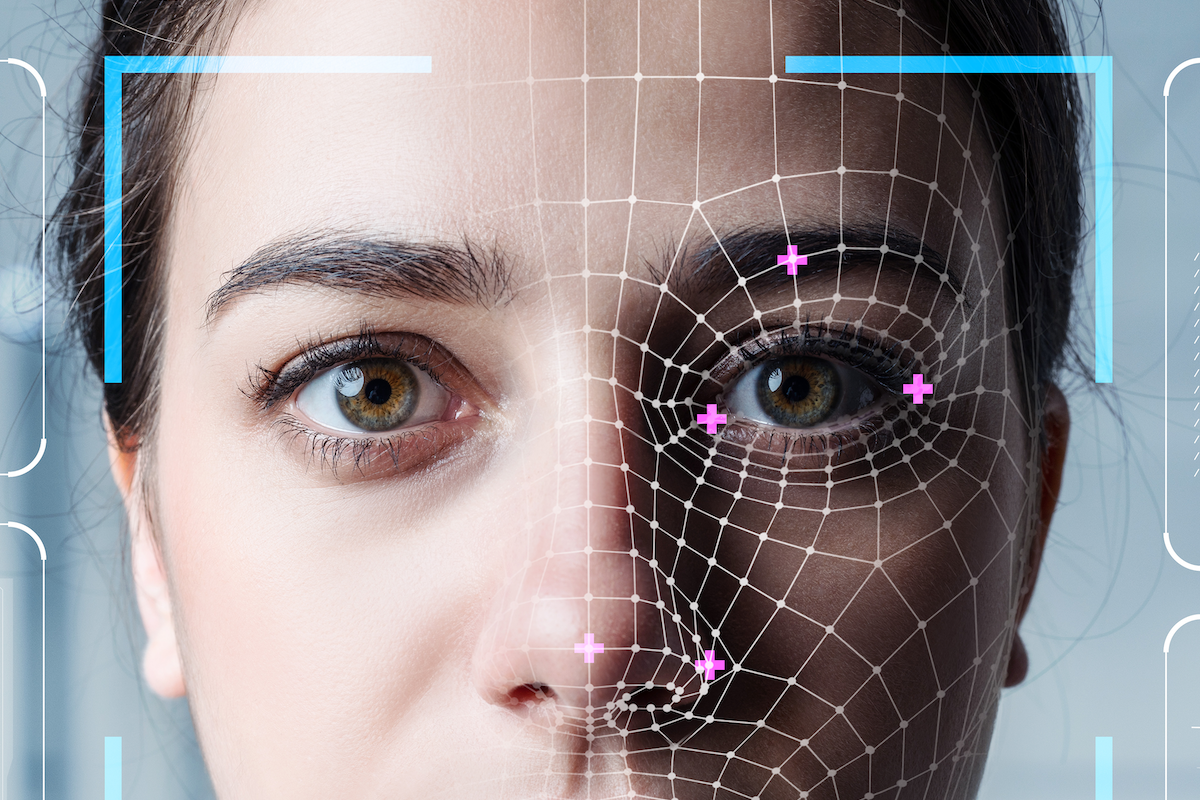

"Take it off your phone,” Danielle Citron responded to a question about facial recognition technology during her keynote at Emory Law’s 40th annual Thrower Symposium on February 4, 2021. “As I look into the camera, pleading — like at this moment — take it off your phone.”

Citron’s appeal was a powerful punctuation following her descriptions of the types of harm caused by invasions of “intimate privacy:” the unreliability of facial recognition technology, revenge porn sites operating in the United States, the use of deep-fake sex videos by governments to silence opponents, suicides in the wake of leaked data from the Ashley Madison hack, the invasive prospect of increased insurance premiums caused by health data shared with insurers, and the risks to women and margin-alized communities by male-centered app development.

A MacArthur Fellow and pioneer in the field of digital privacy, Citron is the Jefferson Scholars Foundation Schenk Distinguished Professor in Law at the University of Virginia School of Law. Her work encompasses cyber stalking, sexual privacy, information privacy, free expression, and civil rights. Her keynote underscored one of the largest themes of the day: that individuals constantly share large amounts of personal data on a daily basis, are not aware of the many ways it may be used, and are significantly under-protected.

Throughout the symposium, called “Privacy in the Technology Age: Big Tech, Government, and Civil Liberties,” panelists discussed the limits of legislation as technology has advanced and become inextricable from modern life, often concluding that existing laws are insufficient.

In order to “secure the future for intimate privacy,” Citron proposed two changes to American law: a need for comprehensive data protection law, and the desire to protect intimate privacy as a matter of civil rights. Additionally, she addressed Silicon Valley, calling on them to abandon their “hacker’s ethos,” in which she says developers beta test everything to see what sticks, but “worry about harm later,” and instead adopt a practice of considering privacy harms in the “design stage.” “We no longer do that for automobiles,” she says, “We should not do that in the case of privacy and intimate privacy.”

Initially inspired by significant 4th Amendment cases at the Supreme Court and data breaches frequently reported in the news, like those involving Equifax and Home Depot, Colby Moore 21L, executive symposium editor for Emory Law Journal, helped form the theme for February’s event. “And then the pandemic hit,” he remarked, “and it became clear that ‘Privacy in the Technology Age’ was the right fit.” As Citron and other panelists also noted, Moore says, “More than ever before, technology became the way we attend class, go to work, communicate with loved ones, visit the doctor, etc. Even though we were hopeful at the time that the pandemic would be over when the 2021 Thrower Symposium took place, we knew our lives and relationship with technology had changed permanently.”

For Northeeastern University School of Law professor Woodrow Hartzog, US policy has been limited for decades by “path dependency,” the idea that although maybe a solution previously implemented wasn’t the best or most efficient option — the qwerty keyboard or the tradition of building power lines above-ground — established precedent compels future action, and change is difficult.

In the first panel of the day, “Personal Data Protection: How Technology Jeopardizes Privacy,” Hartzog asked, “What if in the 1970s, our idea of building all of our frameworks around this idea that we should have control over personal information, and that we should give consent before anything happens with our data, isn’t actually the best path for data privacy in the United States?” He suggests, “…[T]here’s good reason to believe that consent … is not only impos-sible or impractical at scale, but also that it doesn’t solve the right problems, that it doesn’t protect social values and vulnerable populations, and that, in short, it is no match for the personal data industrial complex.” Hartzog argued, “Path dependency limits our imaginations about what the world could be like.” He suggested, “We’re so focused on this individual autonomy that we miss out on questions like, ‘How do we go about properly valuing what our life was like before smartphones?’”

During the “Surveillance and the 4th Amendment” panel, Jennifer Lynch, surveillance litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, focused many of her comments on how the law struggles to keep up with technological advances and the time it can take for change. In her role, she says, she explains technology to courts and persuades them how to apply or not apply old fourth amendment case law in the best way. “That’s really what I find exciting,” she says. “For example, how do you explain to a court that even though we share information with a third party or make our actions visible to the public, we still have an expectation of privacy in that. There’s literally decades of case law against this.” Lynch described making this argument in cases involving historical cell site location data for nearly ten years, receiving positive opinions in state and district courts, and occasionally at the federal appellate level. “But by 2017,” she says, “we had lost this argument at all of the five federal courts of appeals to take up the issue, only to ultimately take home the big prize, with a win at the Supreme Court and Carpenter in 2018.”

Jamil N. Jaffer is the founder and executive director of the National Security Institute, director of the National Security Law & Policy Program, and assistant professor at the Georgia Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School. Jaffer argued that through decades of technological advancement, the Constitution hasn’t yet required change. “The lines that we’ve created, the boundaries of being creative, I think, have served us very well for the better part of 200 years,” he says. “We didn’t throw those core concepts away when we developed a new technology, like the telephone.” As technology progressed, Jaffer noted that legal changes were made with laws like the Electronic Communications Privacy Act and other statutes, but a fundamental change of the Constitution wasn’t necessary. He described the evolution of a more expansive interpretation of the 4th Amendment, so that it is now more protective of individual privacy that protects a person or communications rather than just a physical location or residence.

Additionally, Jaffer discussed encryption technology, and how the US government has been denied access to information after receiving federal court orders because of it, such as in the dispute between Apple and the FBI after the December 2015 terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California. In a pointed statement, Jaffer says, “We are one major terrorist attack, one significant kidnapping, one significant killing of a child away from Congress coming in, intervening, and mandating a technological solution that may not be technologically savvy and may not be as protective as necessary to protect individuals and potentially national security.” Unless the country finds a middle ground, Jeffer warned, it will lead to an unstable situation and bad legislation.

The final panel of the symposium focused on “Antitrust & Big Tech: Consolidation and the Resulting Tension” and was moderated by Emory Law alumnus Lawrence Reicher 08L, chief, Office of Decree Enforcement and Compliance (Antitrust Division) at the Department of Justice. To begin the panel, Reicher remarked on the timeliness of the topic, in a reference to legislation introduced in February by Senator Amy Klobuchar that “would revamp substantive antitrust laws in ways not seen in decades, if not a century.”

After an examination of whether US enforcement agencies are currently able to effectively evaluate competition in cases like Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram, which in December became the subject of a complaint filed by the Federal Trade Commission and 48 states, panelists addressed a question regarding how consumer privacy and data considerations should be addressed in antitrust analyses, particularly in the case of big tech.

Marina Lao, Board of Visitors Research Scholar and Edward S. Hendrickson Professor of Law at the Seton Hall University School of Law, noted that agencies could have evaluated whether a merger might lessen competition related to privacy, but says that antitrust law isn’t well-suited to address privacy concerns. She explained that privacy harms are very difficult to measure, unlike price effects, and that individuals’ wide range of privacy preferences adds to the difficulty.

Roger Alford, professor of law at the University of Notre Dame Law School, expressed his agreement. “Privacy is first and foremost a consumer protection concern and we should have more vigorous enforcement with respect to consumer protections with respect to privacy, including deceptive trade practices by these companies with respect to their representations about privacy.” He also related the issue to fair competition in further discussion, and cited Google’s blocking of third-party cookies as an example, explaining that as a result, publishers no longer have access to information they have always previously known about their subscribers.

Like many other speakers, Alford described the conflict between technology’s efficiency and its potential for harm. “Targeted advertising is efficient in the sense that it’s better than watching a football game and every other commercial is a Ford F-150 pickup truck, and you don’t want to buy a Ford F-150 pickup truck,” he says, “So there is a value to targeted advertising, there’s no question about that; but, it’s the way that they use the privacy controls to advantage themselves over their competitors.”

Chaz Arnett, associate professor of law at the University of Maryland’s Carey School of Law, framed his remarks with a quote from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.”

Arnett referred to the duality Ellison described and explained his intention to connect the quote to the intersection of race and surveillance. He remarked upon “the notion of not truly being seen for what one is, and yet subject to perpetual watchful eyes and gaze distorted too often by deep notions related to skin color.”

Arnett defines racialized surveillance as surveillance that is being used to legitimize and maintain racial hierarchy either explicitly or implicitly through entrenched institutional practices, policies, and regulations built upon white supremacy. He shared some of the points made in his recent law review article, arguing that racialized surveillance practices predate the founding of the US and the drafting of the 4th Amendment and often have less to do with public safety than the maintenance of the racial status quo. He remarked, “Not only has law failed to protect some of the exalted values of liberty and freedom in terms of racial justice and privacy, but also law and law enforcement have been active conspirators in suppressing movements for racial justice and equity through facilitation and licensing of racialized surveillance practices.”

Arnett argued that assumptions of technology as neutral, passive, fair, and efficient negatively impact attempts to limit racialized surveillance. As an example, he described an aerial surveillance program in Baltimore, Maryland, that ended last year. He explained, “It was promoted as neutral because it was surveillance to cover a wide area across the city, and in fact, monitoring could even be used to monitor the conduct of police offers.” However, when maps of flight patterns were gathered, the data showed that the surveillance planes primarily hovered and circled above Black communities.

Anita Allen, vice provost for faculty and Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and professor of philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, explored the risks of social tracking and location monitoring, which she described as “much less discussed and much less regulated” than the unreliability and potential dangers of facial recognition technology. Allen explained that tracking a person’s location shows not only conduct, but can also identify ethnicity, sexual orientation, politics, and religion. She warned, “Globally, the risk of human rights infringements and technological blunder will inevitably fall disproportionately on already subordinated groups, whether African Americans in America or Uighurs in China. Race, gender, religion, caste, and class must matter as societies shape social tracking law and policy.” Allen also noted that “while some jurisdictions have banned official uses of facial recognition technology, regulation of location monitoring remains sparse” and expressed concern that without regu-lation, police could track individuals without a warrant or probable cause.

In spite of the many benefits to social tracking Allen listed in her remarks, from improving health and fitness to supporting law enforcement and national security, she argued, “Social tracking is far from an unmitigated social good.”

Similarly, Lynch also concluded her initial statements by expressing concern about the negative impact of government surveillance. “People who look like me and people who say they have nothing to hide are generally not the targets of arbitrary government surveillance,” she says. “That happens disproportionately in communities of color, immigrant communities, and minority communities.”

Moderator Morgan Cloud, Charles Howard Candler Professor at Emory Law, suggested that because consumers use devices to record information voluntarily, most likely know their personal data is being gathered and used by companies. Allen disagreed, and acknowledged, “So, it’s certainly the case that we, as consumers, are now complicit in the big ‘data grab.’” However, she noted that many people do not read the lengthy terms of service for the apps and websites they use or have a clear understanding that when they use devices, a company may be gathering, using, analyzing, and sharing their data. She says, “I think we’re a long way from being able to say that this … does not merit some paternalistic, as it were, intervention from the government.”

Moore echoed this sentiment when asked what he found most notable about the symposium, saying, “We are constantly told and warned about it, but the symposium really drove home just how much data and information we give away on a daily basis.”

Because big tech companies are overwhelmingly American, Alford says, the United States must deal with antitrust issues, and cited Google as an example. “I think it’s very alarming that Google threatened to basically cut off Australia.”

Citron took a harsh view, and called the US a “safe haven” for websites that she says “engage in and focus on destructive invasions of intimate privacy,” blaming Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. She says site operators enjoy “broad-sweeping immunity from liability for user-generated content,” and says that is the reason revenge porn sites operate out of the US with impunity and why law enforcers in other countries have told her their biggest struggle is sites located in the US.

While the symposium is typically held in Hunter Atrium at Emory Law, the online format of this year’s Thrower Symposium demonstrated the pervasiveness of data collection that panelists emphasized. Weeks after the event, ample data is available at a level beyond what any prior symposium has recorded: automatically produced transcripts, reports on attendees’ engagement and attentiveness, audio recorded prior to the event’s start, and even video of speakers’ homes and offices.

After the event, Moore commented on the importance of the issues discussed to students and practitioners, “Technology and privacy have permeated into every different facet of law. Shaping scholarship on how various areas of the law interact with technology is applicable to everyone.” As each speaker made increasingly apparent, there are many facets of digital privacy law left to shape.

Recordings of the 2021 Thrower Symposium are available on Emory Law’s YouTube channel and at law.emory.edu/elj.

Email the Editor

A MacArthur Fellow and pioneer in the field of digital privacy, Citron is the Jefferson Scholars Foundation Schenk Distinguished Professor in Law at the University of Virginia School of Law. Her work encompasses cyber stalking, sexual privacy, information privacy, free expression, and civil rights. Her keynote underscored one of the largest themes of the day: that individuals constantly share large amounts of personal data on a daily basis, are not aware of the many ways it may be used, and are significantly under-protected.

Throughout the symposium, called “Privacy in the Technology Age: Big Tech, Government, and Civil Liberties,” panelists discussed the limits of legislation as technology has advanced and become inextricable from modern life, often concluding that existing laws are insufficient.

In order to “secure the future for intimate privacy,” Citron proposed two changes to American law: a need for comprehensive data protection law, and the desire to protect intimate privacy as a matter of civil rights. Additionally, she addressed Silicon Valley, calling on them to abandon their “hacker’s ethos,” in which she says developers beta test everything to see what sticks, but “worry about harm later,” and instead adopt a practice of considering privacy harms in the “design stage.” “We no longer do that for automobiles,” she says, “We should not do that in the case of privacy and intimate privacy.”

Initially inspired by significant 4th Amendment cases at the Supreme Court and data breaches frequently reported in the news, like those involving Equifax and Home Depot, Colby Moore 21L, executive symposium editor for Emory Law Journal, helped form the theme for February’s event. “And then the pandemic hit,” he remarked, “and it became clear that ‘Privacy in the Technology Age’ was the right fit.” As Citron and other panelists also noted, Moore says, “More than ever before, technology became the way we attend class, go to work, communicate with loved ones, visit the doctor, etc. Even though we were hopeful at the time that the pandemic would be over when the 2021 Thrower Symposium took place, we knew our lives and relationship with technology had changed permanently.”

EXAMINING LEGAL LIMITATIONS

Weaving a common thread between each of the day’s topics was a discussion surrounding limitations: the limitations of US law to date, the challenges technology like encryption can create for compliance with the law, and the ques-tion of how regulation can or should move forward.For Northeeastern University School of Law professor Woodrow Hartzog, US policy has been limited for decades by “path dependency,” the idea that although maybe a solution previously implemented wasn’t the best or most efficient option — the qwerty keyboard or the tradition of building power lines above-ground — established precedent compels future action, and change is difficult.

In the first panel of the day, “Personal Data Protection: How Technology Jeopardizes Privacy,” Hartzog asked, “What if in the 1970s, our idea of building all of our frameworks around this idea that we should have control over personal information, and that we should give consent before anything happens with our data, isn’t actually the best path for data privacy in the United States?” He suggests, “…[T]here’s good reason to believe that consent … is not only impos-sible or impractical at scale, but also that it doesn’t solve the right problems, that it doesn’t protect social values and vulnerable populations, and that, in short, it is no match for the personal data industrial complex.” Hartzog argued, “Path dependency limits our imaginations about what the world could be like.” He suggested, “We’re so focused on this individual autonomy that we miss out on questions like, ‘How do we go about properly valuing what our life was like before smartphones?’”

During the “Surveillance and the 4th Amendment” panel, Jennifer Lynch, surveillance litigation director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, focused many of her comments on how the law struggles to keep up with technological advances and the time it can take for change. In her role, she says, she explains technology to courts and persuades them how to apply or not apply old fourth amendment case law in the best way. “That’s really what I find exciting,” she says. “For example, how do you explain to a court that even though we share information with a third party or make our actions visible to the public, we still have an expectation of privacy in that. There’s literally decades of case law against this.” Lynch described making this argument in cases involving historical cell site location data for nearly ten years, receiving positive opinions in state and district courts, and occasionally at the federal appellate level. “But by 2017,” she says, “we had lost this argument at all of the five federal courts of appeals to take up the issue, only to ultimately take home the big prize, with a win at the Supreme Court and Carpenter in 2018.”

Jamil N. Jaffer is the founder and executive director of the National Security Institute, director of the National Security Law & Policy Program, and assistant professor at the Georgia Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School. Jaffer argued that through decades of technological advancement, the Constitution hasn’t yet required change. “The lines that we’ve created, the boundaries of being creative, I think, have served us very well for the better part of 200 years,” he says. “We didn’t throw those core concepts away when we developed a new technology, like the telephone.” As technology progressed, Jaffer noted that legal changes were made with laws like the Electronic Communications Privacy Act and other statutes, but a fundamental change of the Constitution wasn’t necessary. He described the evolution of a more expansive interpretation of the 4th Amendment, so that it is now more protective of individual privacy that protects a person or communications rather than just a physical location or residence.

Additionally, Jaffer discussed encryption technology, and how the US government has been denied access to information after receiving federal court orders because of it, such as in the dispute between Apple and the FBI after the December 2015 terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California. In a pointed statement, Jaffer says, “We are one major terrorist attack, one significant kidnapping, one significant killing of a child away from Congress coming in, intervening, and mandating a technological solution that may not be technologically savvy and may not be as protective as necessary to protect individuals and potentially national security.” Unless the country finds a middle ground, Jeffer warned, it will lead to an unstable situation and bad legislation.

The final panel of the symposium focused on “Antitrust & Big Tech: Consolidation and the Resulting Tension” and was moderated by Emory Law alumnus Lawrence Reicher 08L, chief, Office of Decree Enforcement and Compliance (Antitrust Division) at the Department of Justice. To begin the panel, Reicher remarked on the timeliness of the topic, in a reference to legislation introduced in February by Senator Amy Klobuchar that “would revamp substantive antitrust laws in ways not seen in decades, if not a century.”

After an examination of whether US enforcement agencies are currently able to effectively evaluate competition in cases like Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram, which in December became the subject of a complaint filed by the Federal Trade Commission and 48 states, panelists addressed a question regarding how consumer privacy and data considerations should be addressed in antitrust analyses, particularly in the case of big tech.

Marina Lao, Board of Visitors Research Scholar and Edward S. Hendrickson Professor of Law at the Seton Hall University School of Law, noted that agencies could have evaluated whether a merger might lessen competition related to privacy, but says that antitrust law isn’t well-suited to address privacy concerns. She explained that privacy harms are very difficult to measure, unlike price effects, and that individuals’ wide range of privacy preferences adds to the difficulty.

Roger Alford, professor of law at the University of Notre Dame Law School, expressed his agreement. “Privacy is first and foremost a consumer protection concern and we should have more vigorous enforcement with respect to consumer protections with respect to privacy, including deceptive trade practices by these companies with respect to their representations about privacy.” He also related the issue to fair competition in further discussion, and cited Google’s blocking of third-party cookies as an example, explaining that as a result, publishers no longer have access to information they have always previously known about their subscribers.

Like many other speakers, Alford described the conflict between technology’s efficiency and its potential for harm. “Targeted advertising is efficient in the sense that it’s better than watching a football game and every other commercial is a Ford F-150 pickup truck, and you don’t want to buy a Ford F-150 pickup truck,” he says, “So there is a value to targeted advertising, there’s no question about that; but, it’s the way that they use the privacy controls to advantage themselves over their competitors.”

BIG TECH AND VULNERABLE COMMUNITIES

Throughout the day, panelists described the disproportionate impact of privacy harms on vulnerable communities.Chaz Arnett, associate professor of law at the University of Maryland’s Carey School of Law, framed his remarks with a quote from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.”

Arnett referred to the duality Ellison described and explained his intention to connect the quote to the intersection of race and surveillance. He remarked upon “the notion of not truly being seen for what one is, and yet subject to perpetual watchful eyes and gaze distorted too often by deep notions related to skin color.”

Arnett defines racialized surveillance as surveillance that is being used to legitimize and maintain racial hierarchy either explicitly or implicitly through entrenched institutional practices, policies, and regulations built upon white supremacy. He shared some of the points made in his recent law review article, arguing that racialized surveillance practices predate the founding of the US and the drafting of the 4th Amendment and often have less to do with public safety than the maintenance of the racial status quo. He remarked, “Not only has law failed to protect some of the exalted values of liberty and freedom in terms of racial justice and privacy, but also law and law enforcement have been active conspirators in suppressing movements for racial justice and equity through facilitation and licensing of racialized surveillance practices.”

Arnett argued that assumptions of technology as neutral, passive, fair, and efficient negatively impact attempts to limit racialized surveillance. As an example, he described an aerial surveillance program in Baltimore, Maryland, that ended last year. He explained, “It was promoted as neutral because it was surveillance to cover a wide area across the city, and in fact, monitoring could even be used to monitor the conduct of police offers.” However, when maps of flight patterns were gathered, the data showed that the surveillance planes primarily hovered and circled above Black communities.

Anita Allen, vice provost for faculty and Henry R. Silverman Professor of Law and professor of philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, explored the risks of social tracking and location monitoring, which she described as “much less discussed and much less regulated” than the unreliability and potential dangers of facial recognition technology. Allen explained that tracking a person’s location shows not only conduct, but can also identify ethnicity, sexual orientation, politics, and religion. She warned, “Globally, the risk of human rights infringements and technological blunder will inevitably fall disproportionately on already subordinated groups, whether African Americans in America or Uighurs in China. Race, gender, religion, caste, and class must matter as societies shape social tracking law and policy.” Allen also noted that “while some jurisdictions have banned official uses of facial recognition technology, regulation of location monitoring remains sparse” and expressed concern that without regu-lation, police could track individuals without a warrant or probable cause.

In spite of the many benefits to social tracking Allen listed in her remarks, from improving health and fitness to supporting law enforcement and national security, she argued, “Social tracking is far from an unmitigated social good.”

Similarly, Lynch also concluded her initial statements by expressing concern about the negative impact of government surveillance. “People who look like me and people who say they have nothing to hide are generally not the targets of arbitrary government surveillance,” she says. “That happens disproportionately in communities of color, immigrant communities, and minority communities.”

ON CONSUMER UNDERSTANDING

At multiple points throughout the day, panelists remarked on how aware consumers are of the extent to which data they generate is collected and potentially shared.Moderator Morgan Cloud, Charles Howard Candler Professor at Emory Law, suggested that because consumers use devices to record information voluntarily, most likely know their personal data is being gathered and used by companies. Allen disagreed, and acknowledged, “So, it’s certainly the case that we, as consumers, are now complicit in the big ‘data grab.’” However, she noted that many people do not read the lengthy terms of service for the apps and websites they use or have a clear understanding that when they use devices, a company may be gathering, using, analyzing, and sharing their data. She says, “I think we’re a long way from being able to say that this … does not merit some paternalistic, as it were, intervention from the government.”

Moore echoed this sentiment when asked what he found most notable about the symposium, saying, “We are constantly told and warned about it, but the symposium really drove home just how much data and information we give away on a daily basis.”

GLOBAL IMPACT AND RESPONSIBILITY

The way in which the United States regulates data collection, digital privacy, and technology is extremely important.Because big tech companies are overwhelmingly American, Alford says, the United States must deal with antitrust issues, and cited Google as an example. “I think it’s very alarming that Google threatened to basically cut off Australia.”

Citron took a harsh view, and called the US a “safe haven” for websites that she says “engage in and focus on destructive invasions of intimate privacy,” blaming Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. She says site operators enjoy “broad-sweeping immunity from liability for user-generated content,” and says that is the reason revenge porn sites operate out of the US with impunity and why law enforcers in other countries have told her their biggest struggle is sites located in the US.

While the symposium is typically held in Hunter Atrium at Emory Law, the online format of this year’s Thrower Symposium demonstrated the pervasiveness of data collection that panelists emphasized. Weeks after the event, ample data is available at a level beyond what any prior symposium has recorded: automatically produced transcripts, reports on attendees’ engagement and attentiveness, audio recorded prior to the event’s start, and even video of speakers’ homes and offices.

After the event, Moore commented on the importance of the issues discussed to students and practitioners, “Technology and privacy have permeated into every different facet of law. Shaping scholarship on how various areas of the law interact with technology is applicable to everyone.” As each speaker made increasingly apparent, there are many facets of digital privacy law left to shape.

Recordings of the 2021 Thrower Symposium are available on Emory Law’s YouTube channel and at law.emory.edu/elj.

Email the Editor