Judicial decision-making

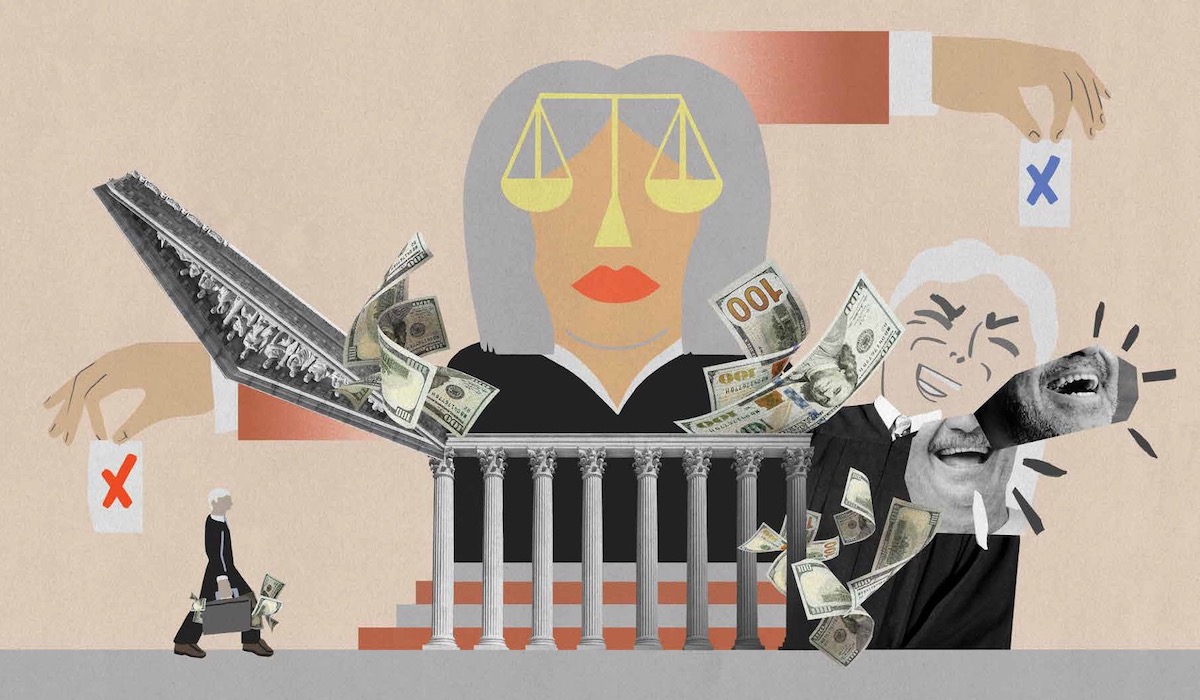

THE U.S. SUPREME COURT’S 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission did more than just open the floodgates for billions of previously restricted campaign contributions— so-called dark money from unnamed donors—to influence state and national elections.

The high court opinion also challenged ideas around judicial decision-making, the long-revered process in which judges interpret, weigh, and apply legal principles to help determine the structure and outcome of a case. While experts say that personal, ideological, and political factors are bound to figure into a judge’s logic, there are new pressures affecting elected jurists in light of the landmark ruling.

“It basically means you can get as much justice as you can buy,” says Joanna Shepherd, Thomas Simmons Professor of Law, who notes that until the1980s judicial candidates often ran uncontested and sometimes didn’t raise a single dollar in campaign funds. “True justice is at risk if the people who contribute more to judges’ campaigns get more justice when they’re in court, and that doesn’t really sound like justice to me.”

Emory Law’s cadre of legal experts turned social scientists

Shepherd is one of many cross-disciplinary scholars at Emory who are researching the changing face of judicial decision-making through the lens of the social sciences. While law schools around the country are known to discuss how judges arrive at decisions, few programs take a deep dive into the dynamics affecting decisions.

Citizens United isn’t the only factor influencing judicial decision-making.

In recent decades, state tort reforms, initially promoted by business lobbies, influenced special interests in other ways. From the 2000s to early 2010s, single-issue plaintiff groups—such as those supporting gay marriage bans—launched an “onslaught” of campaign contributions to judicial candidates friendly to their aims, Shepherd says.

With former Emory Law Professor Michael Kang, Shepherd wrote a book—Free to Judge: The Power of Campaign Money in Judicial Elections—that highlights challenges to judicial decision-making.

The authors propose a solution: elect judges to a single, lengthy term, say, 14 years—the average duration of a state supreme court judge. Judges who don’t face reelection are more likely to make decisions closer to the law than be influenced by political forces, says Shepherd, who teaches a course on torts.

“Reelection is unique to America, and we propose getting rid of that,” she says. Most countries, she notes, don’t elect judges at all.

Jonathan Nash, Robert Howell Hall Professor of Law, also gives judicial decision-making a twist. His course, Judicial Decision-making, considers judicial decision-making beyond the letter of the law.

“It merges legal understandings, which most students have, with information and insights from social science,” he says. “So while most law classes look at what the law says the outcome of a case should be, we look at how the judge’s background might influence a case and resolve an issue.

“It could be gender, it could be religious background, it could be which law school you attended,” Nash adds. “Judges are humans wearing robes. Decision-making can go off the rails when these other factors overtake legal considerations.”

Still, Nash and Shepherd say there are studies that show judges are, for the most part, following the law. Perceptions endure that justice is transactional, however. As for the Supreme Court, Nash notes that some of his students think the body is “entirely political,” but “I think the class actually dispels that quite a lot.” Other students believe that court operates wholly based on judicial rectitude.

The course considers lower courts and how judges are selected.

Students are asked to consider a number of questions. How are jurisdictions filling judgeships? Are there better or worse ways for doing so?

How can positions be filled while minimizing the risk of politicizing the bench?

Two cases that often are identified as politically influenced are those involving abortion, and the 2000 Supreme Court opinion in Bush v. Gore, in which justices controversially ended a Florida presidential ballot recount, allowing a vote certification by state leaders and giving Bush the presidency. The decision remains controversial.

Nash urges caution in weighing abortion decisions, for example. “A judge may think, ‘this is just my approach to judging that leads me to this conclusion, and it happens to align with the theological movement, but I’m not voting based on ideology,’” he says. “They might be masking that in their own mind, or it might actually be true. It’s very hard to pick apart.”

In his course, Nash has students listen to Supreme Court arguments in real time. Students draft opinions and have accurately predicted outcomes in each case, evidence that suggests the law plays a substantial role in results.

Nash developed an interest in judicial decision-making while pursuing his doctorate in political science while teaching at Emory Law. His class draws social science students who are interested in learning how the law intersects that discipline.

“Students find it interesting, and it opens lawyers’ eyes to how judges might be thinking,” Nash says. “That’s important to factor in. Taking a class like this prepares them for a clerkship, and I think when judges see it on their transcript, it shows that they’ve thought about judicial decision-making at a different level.”

Critiques of judicial decision-making aren’t new, but the depth and number of those critiques has expanded since the dawn of the new century. Nash says some of the earliest conversations came 75 years ago, “when political science was becoming more empirical.” The academic world began to see the synergy of law, economics, and social science, he notes. Research opportunities have expanded at the same time computing power and machine learning have developed deeper insights into data sets.

The emergence of the annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies more than two decades ago has united the disciplines and created “more bridges” to combine research. Emory will host this year’s conference in November.

Laughter at the highest court

One example of this new generation of scholar is Tonja Jacobi, professor of law and Sam Nunn Chair in Ethics and Professionalism. She holds a law degree and a doctorate in political science.

Her 2019 study, Taking Laughter Seriously at the Supreme Court, considered how levity is not all as it seems. The groundbreaking research, co-written with Emory Professor of Law and Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data Science Matthew Sag, received global press coverage.

The pair studied every instance of laughter in oral argument transcripts between 1955 and 2017—6,864 incidents in 9,000 cases, they found. The researchers wrote that so-called lighthearted jesting was often used by senior justices as rhetorical tools against less experienced justices to influence decisions.

“It’s basically picking on the loser or picking on the person you don’t like or who you’re going to vote against,” Jacobi says. “We also showed it’s part of a trend of the judicial strategy for the justices to act more like advocates themselves and push particular views. They use laughter to basically mock the argument they don’t like and undermine it in that way. It’s not really about humor at all; it’s about derision.”

Supreme Court Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor is reported to have read the study, and she noted at the time that the paper influenced her colleagues’ behavior. “Some of the male justices apologized to her, and the chief justice started acting more as a referee,” Jacobi says.

A subsequent article by the researchers indicated the paper “didn’t have as much of an effect as Sotomayor described.” Adds Jacobi: “The gendered interruptions actually continue to this day.”

Her research relies on prior sociological and psychological studies that show powerful people, traditionally men, interrupt more and view their speech as “more important.” While change may be slow to come at a hidebound institution such as the Supreme Court, she’s encouraged that people are at least talking about how interruptions and laughter can affect judicial decision-making.

Jacobi highlights such dynamics in her seminar course, Supreme Court Decision-making, which focuses on oral arguments. Students listen to oral arguments and analyze cases for prejudices.

When Jacobi began teaching law at Northwestern Law a decade ago, she said students graduated law school without ever having listened to an oral argument.

“Oral arguments are really important, because they’re a window into how justices make decisions,” she says. “If you’re an advocate, you need to understand this to know how to play the game and be an effective attorney.”

Similarly, Kevin Quinn, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law, has been researching judicial decision-making for more than 25 years, relying on the growing field of natural language processing.

The machine learning technology allows computers to interpret, manipulate, and comprehend human language. In ongoing research, Quinn is using the technology to research how randomly assigned three-judge panels on the U.S. Court of Appeals will likely rule on a matter.

“It’s pretty close to a randomized experiment that allows us to ask questions and get pretty good answers,” he says. “What we were looking at is the propensity to cite past cases.”

Quinn joined Emory last year and splits his time between the law school and the Department of Quantitative Theory and Methods at Emory.

“There’s a really strong group of people here at Emory, both in the law school and in other units on campus, studying judicial decision- making, and that’s rare,” he says.

Email the Editor