In the zone

Securing the grant was ringing affirmation of Emory Law scholarship; the school does not typically receive money from groups that fund scientific research.

The two scholars were sharing a bite at Emory Village’s Rise-n-Dine in 2009 when a question arose between them that few had asked in nearly three decades.

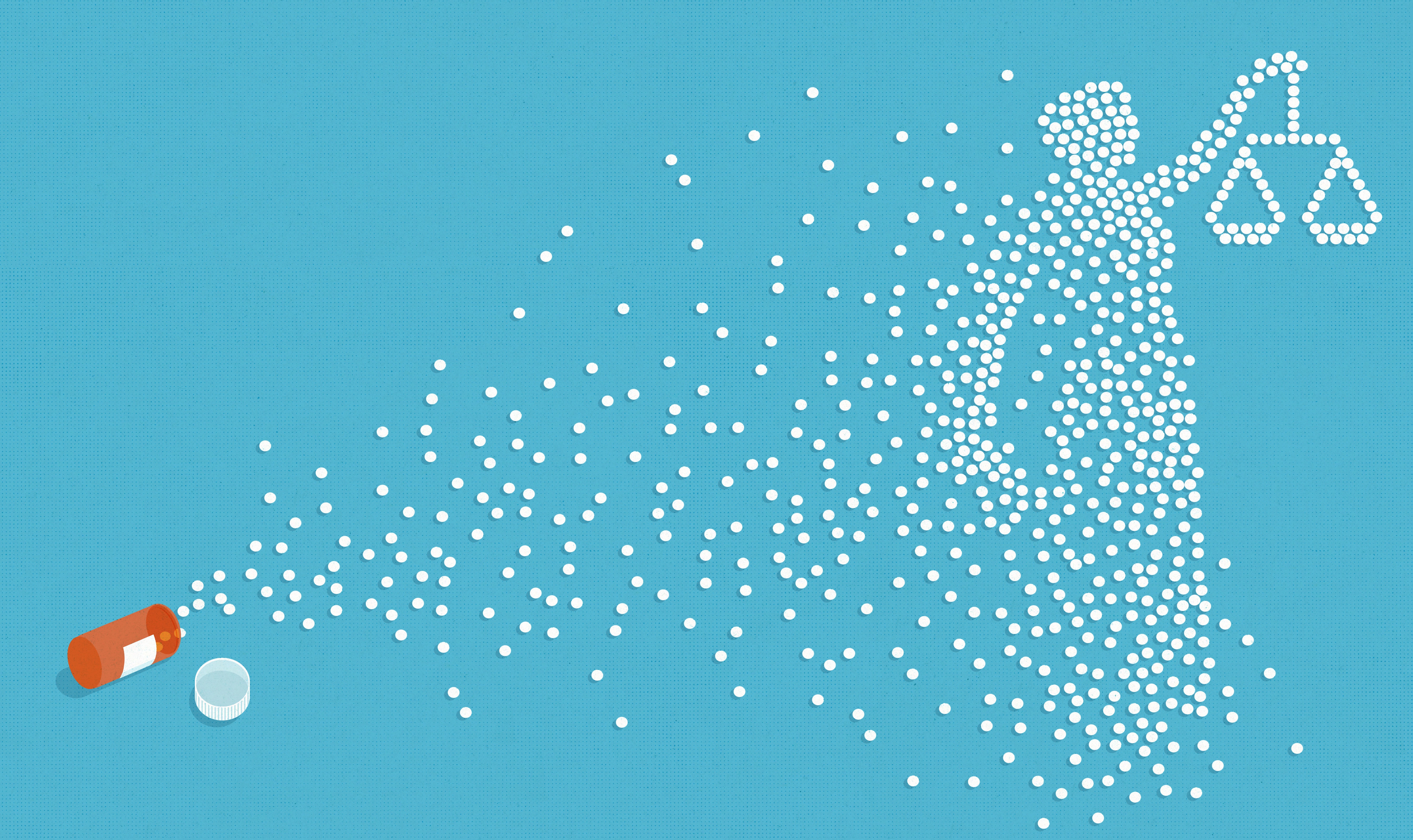

What impact do state drug-free zone laws have on their communities? The laws, developed in the 1980s at the dawn of the so-called “war on drugs,” prescribe heightened penalties for convicted drug dealers who sell illicit substances within, in most cases, a thousand feet of schools, parks and public housing.

“This neutrally designed law,” Emory Law Professor Kay Levine posited, “might have hugely differential impacts, depending on where it is being enforced. It’s a thousand feet, whether you’re at a farm, or in a suburb, or in a city.”

Levine and three colleagues with criminology and sociology backgrounds set out to gain a clearer picture.

In a forthcoming 40-page study, “Race, Place & Discretion in the Handling of Drug-Free Zone Charges,” Levine and former Emory sociology Professor Elizabeth Griffiths, along with two Georgia State University criminologists, Joshua Hinkle and Volkan Topalli, show that inner-city Atlantans do, in fact, face greater legal jeopardy than those living elsewhere in Fulton County.

“Drug-free zone laws, we argue, are problematic in that, if they are followed, they can create these really disparate effects for communities of color,” says Griffiths, now an associate professor of criminal justice at Rutgers University.

It’s what some criminologists and social justice advocates describe as the “hyper-criminalization” of drug offenses, in which people of color and economically disadvantaged residents are disproportionately affected. The scholars hope their work will spur similar research throughout the country. While it’s long been assumed that dense inner cities bear a heavier burden as a result of drug-free zone laws, the group’s work is the first to confirm that’s the case.

"Anywhere in an inner city is going to come close to being within a thousand feet of a school or park or public housing,” says Levine, who helped secure a $400,000 National Science Foundation grant to fund the study, which focused on Fulton County. “That means every drug sale crime in the inner city is subject to these huge penalties, while people in the suburbs and rural areas simply don’t face them.”

More than half of the city of Atlanta falls within a drug-free law zone; outside of the city, a third of Fulton County is in such zones. Penalties are formidable. In Georgia, the statutory maximum penalty for the first violation of a drug-free zone law is 20 years in prison and a $20,000 fine.

Highlighting disparities could help advance the rule of law “by inspiring legislators to seriously rethink having this drug-free zone law on the books in its current form,” Levine says. “I think our study could help legislators be more responsible and more modest in their aims.”

The research team’s six-year effort, which culminated in March of this year, broke new ground in law and criminology, as the team embarked on a “mixed-method” study that involved not just statistical analyses, but also interviews with drug dealers, the police, and prosecutors.

“We really got a full picture of how the drug-free zones work, how they operate, and whether they’re effective,” says Topalli, whose scholarly research addresses violence in urban settings, with a particular focus on the decision-making of street criminals. “It’s not easy to do this kind of work because identifying offenders that are willing to talk to you is not a simple exercise. But it’s well worth it, because the data that they give you is very valuable.”

The team also relied on quantitative spatial analyses - using mapping software and arrest records - to illustrate areas considered to be hyper-criminalized.

Securing the grant was ringing affirmation of Emory Law scholarship; the school does not typically receive money from groups that fund scientific research.

“For us, it’s a big deal that an outside agency says, ‘there’s real value in this work, that you have the capacity to do something maybe game- changing, and we want to be a part of that,’” Levine says. “Our goal is, we wanted to be the first serious researchers to take a look at how these laws are working. The NSF has been an outstanding partner in this research, and they’ve been supportive of us all the way through.”

While the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office doesn’t have a track record of turning over data to social scientists, DA Paul Howard 76L did just that: He shared with the researchers 19,063 felony drug arrest records between 2001 and 2009. Levine and her team found that about 5,000 drug dealers could be subject to extra drug-free zone law penalties. Significantly, almost none of the penalties were levied, in large part because police, the district attorney’s office, and judges decided the time necessary to do so was too burdensome. Or officials said they simply don’t know about provisions.

“We have no idea if Fulton is typical or atypical in terms of the enforcement patterns that we found,” Levine says.

Drug-free zone laws continue to this day to be mostly unenforced in Fulton County. They are considered a “dead letter,” the legal definition for a law that is not enforced. Cell phones and the advent of social media have caused many open air drug markets in drug-free zones to vanish, as dealers favor more discreet transaction methods, Levine notes.

As the laws were envisioned, they would keep drugs out of areas where children congregate, protect children from exposure to drug use, and foster safe public environments. That they remain on the books, regardless of the almost nonexistent current enforcement status, concerns Levine.

“If the prosecutor’s office decided to take a different approach here, and the judges went along with it, the results for the inner-city populations of Fulton would be disastrous,” she says. “I mean, it would shock the conscience what would happen to people caught selling or distributing drugs.”

In the rare cases that police did file a charge against an offender, “it was a very obvious case of a drug deal going down inside of a school,” says Hinkle, whose specialty is evidence-based policing. “But from my interviews, police rarely filed them, and they weren’t using [drug-free zone laws] to target their activities or anything.”

Many have criticized the war on drugs, with the New York Times opining in 2017 that it “has been a failure that has ruined lives, filled prisons and cost a fortune.” Some observers have called on lawmakers to decriminalize small-scale drug possession - some of the very infractions targeted by drug-free zone laws.

“Because of how disproportionately drug-free zone laws cover poor, minority areas, it would certainly be a dangerous law if they started enforcing it and cracking down and making arrests,” Hinkle says. “Even if they’re not being enforced, we shouldn’t ignore them. A new district attorney could come in, and decide they want to start prioritizing those charges.”

Across the United States, legislators over the years have been criticized for enacting criminal law without the benefit of evidence, being motivated instead by political calculations. There also are concerns that drug-free zones result in over-policing of neighborhoods, stigmatizing some areas as drug-ridden when maybe they are not.

“We did not write this (study) up with an eye toward cattle prodding,” Levine says. “We’re hoping it forces a reexamination, as in, ‘I don’t think this law needs to be on the books anymore.’ Clearly, right now in Fulton County, it doesn’t make any sense to anybody to use this law.”

The laws are not thought to be a deterrent, and even the drug dealers who the team interviewed were unclear on their specifics. Some thought the zones started 5,000 to 10,000 feet away from a school, for example. Others, according to the study, incorrectly assumed that drug-free zones included areas near churches and hospitals.

Congress created the first drug-free zone law in 1970s, increasing penalties for certain drug offenses committed near schools. Twelve years later, President Reagan’s “war on drugs” spurred all 50 states and the District of Columbia to adopt their own drug-free zone laws. Except for a handful of limited-scope studies on drug-free zones, they have mostly avoided serious scrutiny.

“While there has been a ton of work, at least in the social sciences on the various types of policies that emerged out of the war on drugs - and beyond that, helped to contribute to mass incarceration - there has been very little work done on drug-free zones,” Griffiths says.

Topalli doesn’t demonize the laws, but neither does he see their value.

“I think most of this legislation was well meaning, but it wasn’t tested ahead of time,” he says, noting a law’s efficacy can be hindered by its own opacity. “It’s very difficult for something to be a deterrent if people aren’t really aware of what the borders and limitations are. It’s not like offenders carry measuring tapes with them. But the distance of a drug-free zone is just not something that’s particularly important to them. They’re much more concerned about competition from other drug dealers.”

The big takeaway from the study, Topalli says, “is that drug-free zones are not particularly effective. It’s very difficult for us to see how they could be made to work better.”