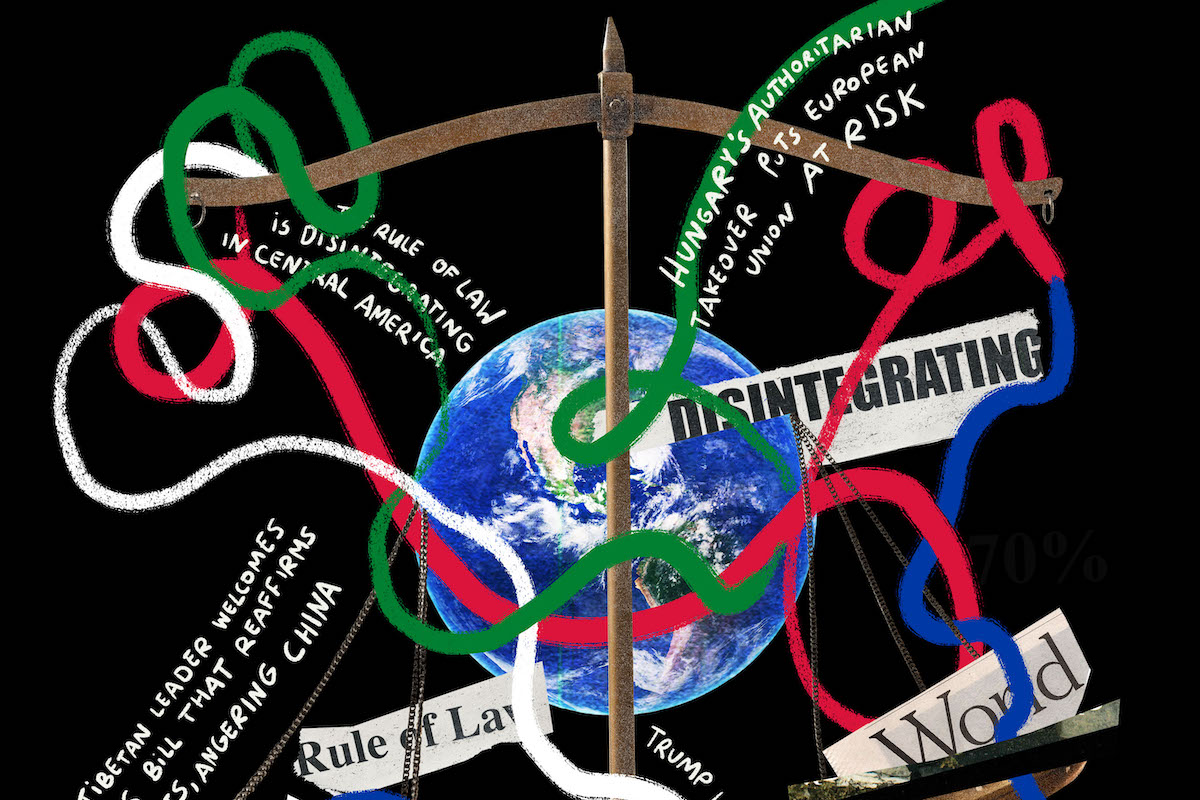

The Rule of Law Abroad

The headlines point to a new and challenging reality in the international legal landscape: between 2015 and 2022, 64 percent of countries experienced declines in the rule of law, according to the World Justice Project (WJP), a Washington, DC-based nonprofit that works to advance rule of law precepts around the globe.

A dozen legal scholars from Emory and beyond considered the ramifications of this decline at this year's Randolph W. Thrower Symposium, held February 2 and hosted by the Emory Law Journal. The event—this year titled "The Future of America's Efforts to Promote the Rule of Law Abroad"—is named after the late Emory Law alumnus and Internal Revenue Service commissioner.

Everett Stanley 23L, editor-in-chief of the Emory Law Journal, called the rule of law "one of those towering ideals that ascends above politics and aspires for universality." It applies to all persons, he continued, in language that is "clear, noncontradictory, predictable."

"These principles .. . have long been principles that America, at least in rhetoric if not reality, has aspired to uphold and promote optimistically," Stanley said.

Panelists weighed in during a trio of sessions that explored contemporary threats to the rule of law, the definition of the rule of law, and ways to advance the rule of law. The current challenges, panelists noted, are profound.

"It is well known that we are in the midst of a global rule of law recession, characterized by closing space for media and civil society, declining trust in institutions, and an increased prevalence of authoritarian governance, even in established democracies," said keynote speaker Elizabeth Andersen, executive director of the WJP.

"We cannot expect to be able to lead a resurgence of the rule of law unless we are credibly working to strengthen our own norms, institutions, and practices. On this, there is much to be done," added Andersen, who previously led the American Bar Association's Rule of Law Initiative, which works in more than 50 countries to advance the rule of law.

In WJP's detailed and comprehensive Rule of Law Index, most recently released in 2022, the United States ranked No. 26 out of 140 countries studied for the accessibility and affordability of its legal system. It ranked No. 120 for discriminatory practices in the civil justice system.

"As academics, lawyers and soon-to-be lawyers in this room, we need to own that failure and its implications for trust in institutions and our democracy," Andersen told the in-person and Zoom audience.

PANELISTS CONSIDERED THREATS to the system of laws that are meant to make public and private actors accountable for their actions: populist movements sweeping nations that include Poland, Hungary, Turkey, and Brazil and the persistence of authoritarianism in China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran. The attack on the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021, also was highlighted as a threat to foundational legal norms.

"Though its exact contours aren't always clear, the rule of law is something that most of us find worth promoting, worth protecting, worth preserving," Emory Law Journal Executive Symposium Editor Eric Wang 23L said in introductory comments. "Perhaps the mean ing and importance of the rule of law grows when we sense that it is threatened, whether abroad or at home."

The WJP poses some defining guidelines that are similar in scope to those supported by the United Nations. Andersen said the rule of law typically ensures checks and balances on the body politic, as well as provides order and security within a society, regulatory enforcement, and civil and criminal justice. The rule of law also is characterized by open government, fundamental rights, and the absence of corruption.

But the rule of law can be measured in myriad other ways. Andersen explained that WJP surveyed 100,000 global households, posing more than 550 questions in which respondents were asked for their assessments of civil and commercial law, criminal and constitutional law, labor law, and public health. They also were asked if they had any interactions with the police in the past year and whether they were solicited for a bribe while registering a child for school.

Half of the survey respondents reported having a serious legal problem in the prior year with some of the most common travails centering on housing and debt. Oftentimes, their legal problems went unresolved. As a result, 29 percent of that group reported stress-related physical ailments or illnesses. A majority of those affected came from poor and marginalized populations, according to WJP.

Many citizens of countries where the rule of law is suspect or absent-71 percent-did not turn to lawyers or courts to solve a legal problem because they were unaware that they had rights to. Additionally, "the pandemic was particularly hard on the rule of law, as governments asserted emergency powers," Andersen noted. "Rights of assembly were curtailed, courts closed, and justice delays mushroomed. The decline in the rule of law has been evident in every region of the world, in rich and poor countries alike."

The WJP suggests the brightest hope for the rule of law can be found in Europe, where the European Union has explicitly written rule-of-law requirements into its founding documents, laws, and regulations. EU standards have served as a powerful incentive for rule-of-law progress in nations such as Moldova and Kosovo, which hope to earn EU membership by undertaking meaningful legal reforms.

"Rule of law rhetoric is very much invoked these days, frequently and sometimes cynically," Andersen said. "Everyone wants to claim that the rule of law is on their side. This capacious and complex subject is vulnerable to being co-opted and even weaponized."

The private sector, propelled by the US Chamber of Commerce's new Rule of Law Coalition, is playing a critical role as a "standard bearer" in ensuring the rule of law, Andersen asserted. In the past decade in particular, more companies are taking seriously the role of human rights and environmental ill)pacts in the way they do business. They've been driven in large part by socially minded investors.

"Increasingly, global businesses across diverse sectors see the rule of law as a bottom-line issue," Andersen said. "It's no longer just a nice-tohave, but a need-to-have. And this gets the attention of governments and policymakers who must embrace systemic reform."

It's a dynamic that has played out in surprising corners of the world, like the Central Asian countries of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, both of which have made year-over-year advances in the rule of law since 2015. Andersen urges businesses to identify effective governance approaches and advocating reforms in nations where they might invest. Global investors routinely use WJP's index in their decision-making.

While many public-private partnerships have evolved around being good stewards of the environment, WJP advocates creating a more "people-centered" approach to the rule of law, an attempt to ensure access to justice for all. "A people-centered approach to justice prioritizes prevention," Andersen says. "We might prioritize, for example, solving the problem of the 1 billion people globally who lack proof of legal identity. The good news is that this kind of people-centered approach is catching on."

ASSAULTS ON THE RULE OF LAW occur in calculated ways by governments who want to limit the impact of dissidents, said panelist Martin Flaherty, a professor of law and founding co-director of the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice at the Fordham University School of Law.

"One thing that backsliding regimes tend to do is focus on the persecution of lawyers, human rights lawyers in particular, for a fairly obvious reason," he said. "You persecute a dissident, (then) you persecuted the dissident. You persecute a lawyer, and you persecute all of the dissidents that lawyer represents. There's a multiplier effect. Authoritarian regimes know that."

Flaherty highlighted China's adoption of the rule of law in the 1990s, since doing so is critical toward creating a modern market economy that encourages foreign investment. In 1980, he said, China had "virtually no law schools and virtually no lawyers." Today, there are around 400 law schools, with more than 300,000 lawyers in the country.

"But the eagerness on the part of the [ communist] party and the government for outside legal input started to plateau not long before the [ 2008] Beijing Olympics," Flaherty said. "It became clear to the leadership that law had become a double-edged sword; that it could promote order, it could promote foreign direct investment, but it could also be used by those within China who took it seriously, as a way to vindicate criminal defense rights, the rights of the disempowered, and health care rights."

Lawyers then become "enemies of the party and the state," he added, "and an array of persecution is deployed against them. So, basically, the space for any independent lawyering from China is closed. There are a lot of lawyers and activists in China who are laying low."

Lack of rule of law protections has made it possible for China to house in "reeducation camps" up to 1.5 million Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group native to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China. The Chinese government has been accused of human rights abuses and genocide in its treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities. Political actors such as President Xi Jin ping of China, whose "Thought on the Rule of Law" treatise rejects an independent judiciary and characterizes the principle of separation of powers as "erroneous Western thought."

The trends away from the rule of law follow more than three decades in which the global community was in consensus that democracy and human rights are central to the political legitimacy of governments, said David Carroll, director of the Democracy Program at The Carter Center. The program attempts to strengthen participatory democracy, especially for historically disadvantaged groups, or people who face political, cultural, or socioeconomic barriers.

One way to protect the rule of law is to encourage international election observation, an activity in which President Jimmy Carter has participated. The practice has expanded dramatically in the past 40 years, Carroll said, particularly in countries where human rights are a concern. Elections, by their very nature, are meant to be tools for transparency in which people can see and understand their government and have confidence in institutions.

"It's appropriate for there to be observers who come and independently look at an election process and objectively provide some information about that," Carroll said. "There has been a development of a community ... of groups that do this kind of work. We're interacting more and sharing experiences and talking about the challenges we face in trying to provide that informational role [to] the rest of the world."

CHALLENGES TO THE RULE OF LAW are expected to persist, as the United States is no longer the single dominant global power, Carroll noted. Apart from China and the United States, "there are also middle powers who are increasingly assertive and staking their interest on the global stage," he added. "That is part and parcel of this threat to the norm and institutions of the liberal international order."

He warned against the rise of "electoral autocracy," in which "elections look like elections on the outside, but they're not really genuine." As a result, there are weaknesses throughout government institutions, Carroll said.

Since 2012, the number of liberal democracies has declined every year-from 42 to 34; 70 percent of the global population lives in countries that are ruled by an autocrat, according to Carroll. "There are authoritarian states that are trying to provide an alternative political model, and to become a center of gravity," he said. "That's part of this threat to the global international order. They are increasingly working in coalitions with one another."

Other participants included Monika Nalepa, professor of political science and director of the Transitional Justice and Democratic Stability Lab at the University of Chicago; Magdalena Tulibacka, faculty lecturer at Emory Law; Mila Versteeg, professor of law and director of the Human Rights Program at University of Virginia School of Law; Brian Tamanaha, professor at Washington University in St. Louis School of Law; Paul Gowder, professor of law and associate dean of research and intellectual life at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law; Hallie Ludsin, faculty lecturer and senior fellow at the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory Law; William Ide, counsel at Akerman LLP and former president of the American Bar Association; Mary L. Dudziak, Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law at Emory Law; Jon Smibert, adjunct professor at Emory Law and former resident legal adviser at the US Department of Justice; and Hillary Forden, senior associate director of the Rule of Law Program at The Carter Center.

Email the Editor