Launched by Emory Law

"Three years of immersion helped develop and sharpen an ability to distill complex situations into their critical elements." - Bill Gisel 78L

Law school is far too rigorous for any prospective student to commit casually to the idea of, “What next? Perhaps law school.” And yet, that’s how many find themselves there. They apply because they enjoy reading, writing, and analytical thinking, and they suspect there must be something more enticing than their current career or the job offers they’re considering after graduation. “There’s no one right way through law school or the profession,” Dean Robert Schapiro says. Some Emory students begin law school confident of their future careers as public defender, prosecutor, or transactional lawyer. Others aren’t so sure. They might be the first family member to attend law school or even college for that matter. “Emory aims to launch people into leadership throughout a variety of careers,” Schapiro continues. “There are many ways they can realize their goals in the legal profession, and those goals can evolve after law school.” An Emory education makes a leader in law and builds a foundation for the first job and for the career that extends over decades and evolves alongside changes in the law.

For those Emory Law alumni who thrive in the career they imagined precisely for themselves 30 years ago, there are others whose time at Emory launched them into unexpected positions of leadership in academia, industry, the judiciary, and law practice. They get there, Schapiro says, through the school’s “robust curriculum and the numerous opportunities for experiential learning and connecting with the profession.” These four stories illustrate the distinct ability of Emory Law to help students determine a path for themselves.

Academia

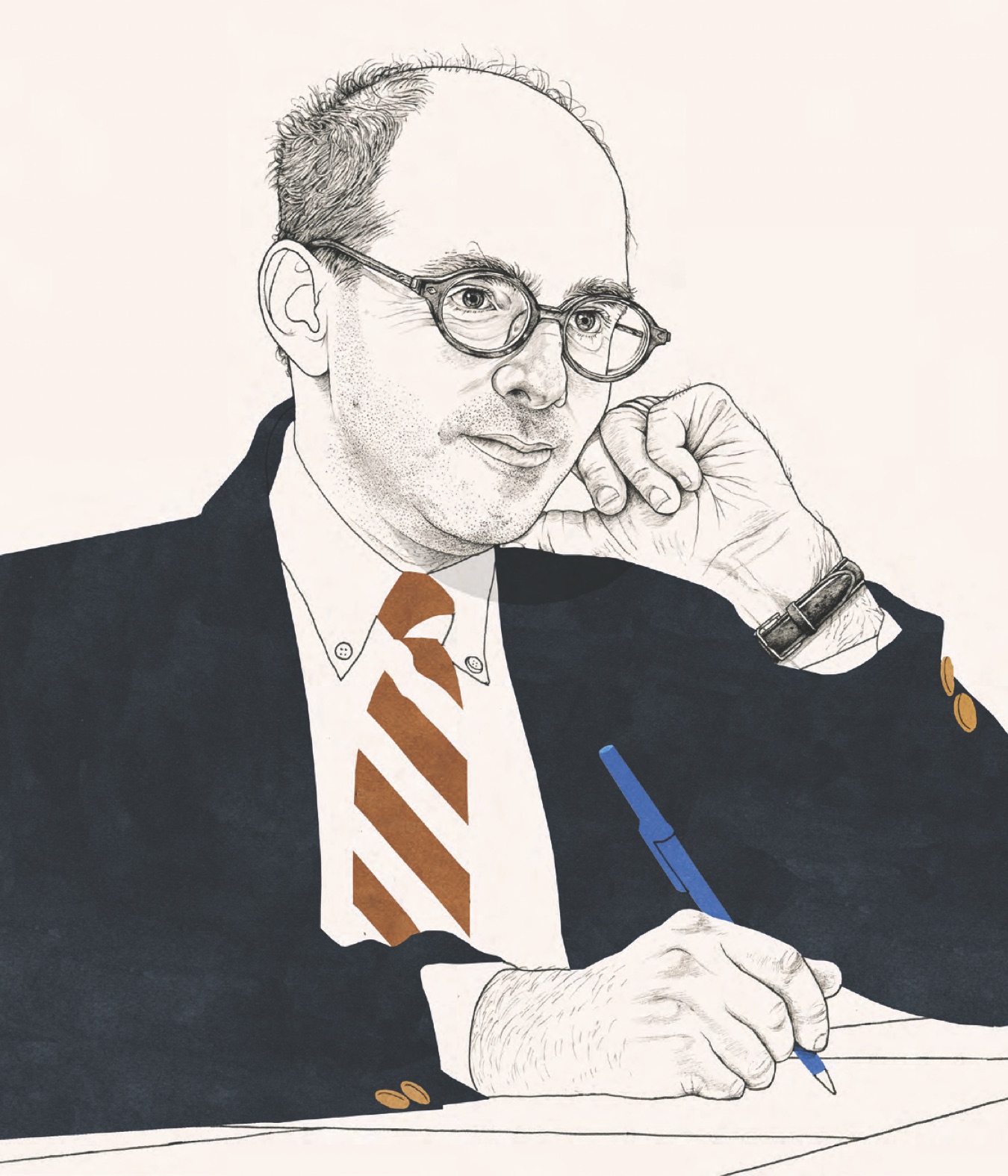

Andrew Klein on Emory’s exceptional faculty

Andrew Klein 88L is dean and Paul E. Beam Professor of Law at Indiana University¿s Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

At the start of law school, Klein was interested in litigation. It wasn’t until his third year, serving as editor of the Emory Law Journal, that he considered academia. “My Emory professors encouraged me,” Klein says. “They pointed out that I was doing - and enjoying - exactly the things academics do by editing the work of law professors and writing my own research paper.” Despite his growing interest in academia, Klein, like many Emory Law graduates, started his career with a judicial clerkship and then practiced at a large firm. While he was doing litigation in Chicago, he realized he was ready to transition into academia. Klein focused his job search to Chicago (his hometown) and Atlanta (his wife’s hometown; he and Diane (Schussel) Klein 88L were in the same section their first year of law school and married two years after graduation). After eight years on the faculty at Cumberland School of Law at Samford University in Alabama, Klein relocated to Indianapolis, where he now serves as dean and Paul E. Beam Professor of Law at Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

Klein still maintains contact with Emory faculty, who continue to mentor him. Those well-established connections have influenced how he counsels students. “I certainly make time for any current or former student who wants to sit down and talk about his or her future. I never say no to that conversation,” he says.

Klein attributes his preparedness for a career in law to Emory’s “excellent classroom teaching.” As he learned at Emory, effective teaching requires more than having students learn black-letter law; they must understand what underlies the law in order to be the best advocates for their clients. This requires sharp problem-solving skills, and Klein’s classroom instruction incorporates a lot of that. When Klein first began teaching, he even used notes from some of his Emory Law classes to outline his lessons. “I wouldn’t have followed this path if I didn’t have people caring about me, as they did at Emory,” he says.

Industry

Bill Gisel on the breadth of an Emory Law education

Bill Gisel 78L is the president and CEO of Rich Products Corporation.

Gisel launched his Emory Law career one day behind schedule, but despite this uncertain start, he immediately found Emory to be an engaging environment and liked his professors and classmates. He took a wide variety of electives; his approach was to learn more about anything that interested him, rather than focusing on any particularly area. “My time there didn’t direct me to one particular type of practice. It was broad-based exposure,” he explains. He didn’t leave Emory with a clear picture of what was next, but he says, “The education actually made me think I could do more things. Three years of immersion helped develop and sharpen an ability to distill complex situations into their critical elements and to deal with very ambiguous and complicated patterns.”

Gisel has spent the past 35 years at Rich, traveling the world and expanding his “range of challenges,” which included helping with the acquisition of a minor league baseball team and rebuilding a stadium that not only influ- enced the designs of other US ballparks but was among the first to include more sophisticated dining options. He marvels at his good fortune to have worked for a family business for 35 years — reporting to the same person — and calls it a luxury. “There’s a range of possibilities here. The diversity within one organization has allowed me to stay here,” he says.

Judiciary

Judge Catharina Haynes on establishing an Emory Law reputation

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Catharina Dubbelday Haynes 86L can trace her passion for justice back to childhood. “As a young child, I was profoundly interested in justice. I had a strong sense of what was fair and right,” she says. At age ten, “I figured out that’s what lawyers do.” She was unwavering in her determination to attend law school, an academic anomaly in a family composed of scientists and educators.

In 1998, she was encouraged to run for an open seat on the Dallas District Court. “I ended up putting my hat in the ring,” she says, “because people I respected thought I had the ability to be a good judge.” She served two terms before returning to private practice as a partner at Baker Botts. Her time as a judge sharpened her perspective of the system. “There were a lot of truths that I knew, but they became more real,” she says. Among them, she cites the importance of writing clear, concise briefs. Haynes elaborates, “There’s a way of looking at things that’s judicial. How will this look to the judge? How will this conduct be received?”

On July 17, 2007, she received her Fifth Circuit nomination by President George W. Bush. She describes the process prior to the nomination as “vetting, vetting, vetting, and background checks.” The experience underscored the fact that professionalism, ethics, and conduct are vital to one’s career in law. “Recognize that from the start of adulthood, your conduct matters,” Haynes says. She attributes this understanding in part to her Emory Law education. “It was drilled into us when we were students interviewing for jobs. As a student, you’re representing Emory and wouldn’t want to detract from Emory’s brand. You need to recognize that you’re being viewed that way at an internship, an interview - and understand the larger picture of what you do.”

The Senate confirmed Haynes on April 10, 2008, and she took her oath of office on April 22. The confirmation process was difficult because of its inherent uncertainty and because she had only been back at Baker Botts for a few months when it began. “It’s a complex position to be in, and, of course, it’s an honor. People would say, ‘Isn’t this hard?’ And I would say, ‘Maybe, but it is a good problem to have. I’m either going to be a Baker Botts partner or a federal judge.’” That attitude of being guided by professional ethics and working even during the duress of the nomination period reflects on those Emory Law lessons of conduct. “It takes a lifetime to build a reputation and a day to lose it,” Haynes reinforces.

Law Practice

Miranda Schiller on the impact of formative experiences at Emory Law

Miranda Schiller 86L is a partner in the Securities Litigation and Corporate Governance practice of Weil, Gotshal & Manges.

The significance of Schiller’s Emory Law education wasn’t just finding the type of law that captured her interest; it was finding a clerkship that produced a lifelong mentor. “Clerking can be the most formative and valuable experience for a young lawyer,” Schiller says. She clerked in Houston for Judge Lynn Hughes, who allowed his two law clerks to trade cases based on what interested them. Schiller’s colleague happily handed over the securities cases. During her clerkship, Schiller worked on a battle for corporate control with Moore McCormack, a case that attracted media attention from the Wall Street Journal and other outlets, eventually leading to appearances on talk circuits for Hughes and Schiller.

After her clerkship, Schiller returned to her home, New York City. “This was the 1980s. There was a perception of New York practice as a sharper, more aggressive, wear-you-down kind of practice,” Schiller says. Yes, it was at times a stressful environment, but Schiller recognized in this career something that had been missing in her first. “Complex securities and fraud cases really interested me and made me excited about coming into work in the morning and talking about it after hours,” she says. “Find a niche you like. Even better if you figure that out early on.” Schiller knows that the length of her career at Weil is unusual; in recent years moving from firm to firm has become more typical.

Another aspect of her Emory experience that she has put to work in private practice is defending a death penalty case she’s been working on since 1989. While at Emory, Schiller had an internship at the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee. As a law student, she “did investigations, helped prepare briefs, and located witnesses who would have testified at trial but were overlooked by inexperienced lawyers.” While in Texas, Schiller worked on a death case that wound up in the Supreme Court and became a seminal case on sentencing instructions. When Schiller arrived at Weil in 1988, she was still interested in these types of cases, but no one had taken a death case in the firm’s pro bono practice. A year later, with Steven Reiss, who had taught criminal law at NYU, Schiller took on a case and has handled it with other associates since 1989. “I’m happy to say my client is still alive,” she says.

Reflecting on the start of her law school career, Schiller can recall the dean’s introductory address to a group of 215 students gathered in an auditorium for orientation. He posed to the group, “Why go to law school with an oversupply of lawyers?” The answer he offered, Schiller says, was, “There’s an undersupply of good lawyers.”

Emory Law makes good lawyers. Its proven formula is strong teaching and deeply caring faculty, combined with a broad curriculum and personalized career advising. Emory makes available opportunities for internships and clerkships - jobs that develop professional conduct and ingrain the idea that to succeed in this industry, one must serve the public. These four alumni are a small sample of the diverse careers that have been forged from an Emory Law education. Ultimately, Emory aims to “provide [its graduates] the foundation in critical thinking and in the professional values and ethics that serve a career in any arena,” Schapiro says. At the time of its centennial, Emory Law can point proudly to 11,472 of them.