Teaching equality

Sarah Tona 17L wrote of an undergraduate student with a neuromuscular disability in the early 1980s who had to crawl up flights of stairs on her hands and knees to register for student housing and to attend her classes.

Their work was part of an unusual seminar that studied Emory’s history through the lens of the students’ own research. The result was not, as Nicole Schladt 18L put it, “triumphalist reflections” on the last one hundred years. Instead, the stories included “invisibility and heartbreak, ... tears and frustration and fear,” as well as the building of community.

Law schools and universities often write their own histories when celebrating landmark anniversaries. These histories tend to have a predictable teleology: an upward path toward a triumphant future. Such works are important efforts to celebrate past milestones. For students whose experience is not on the pages, however, they can be experienced as an erasure. Historical narratives always leave things out, of course. The writing of history requires exclusions. My students did not set out to correct the narrative, but instead to write stories that had not been told.

The Equality at Emory seminar was inspired by Sherillyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, when she delivered Emory Law’s 2016 Martin Luther King Jr. Day lecture. Asked what educational institutions might do to address their own inequalities, Ifill began with: “First, know your history.” As a historian, I took that as a direct order. With Dean Robert Schapiro’s support, I designed a research seminar that would explore the history of inclusion and exclusion at Emory. Teaching this class brought me back to the subject that had attracted me to law teaching in the first place. My first research seminars at the University of Iowa College of Law beginning in the late 1980s were on constitutional and civil rights history. My students used local archives and wrote original papers. Some were published in law and humanities journals. In years since, my writing and teaching have gone in a different direction. I was excited to return to civil rights history and to offer this kind of research experience at Emory.

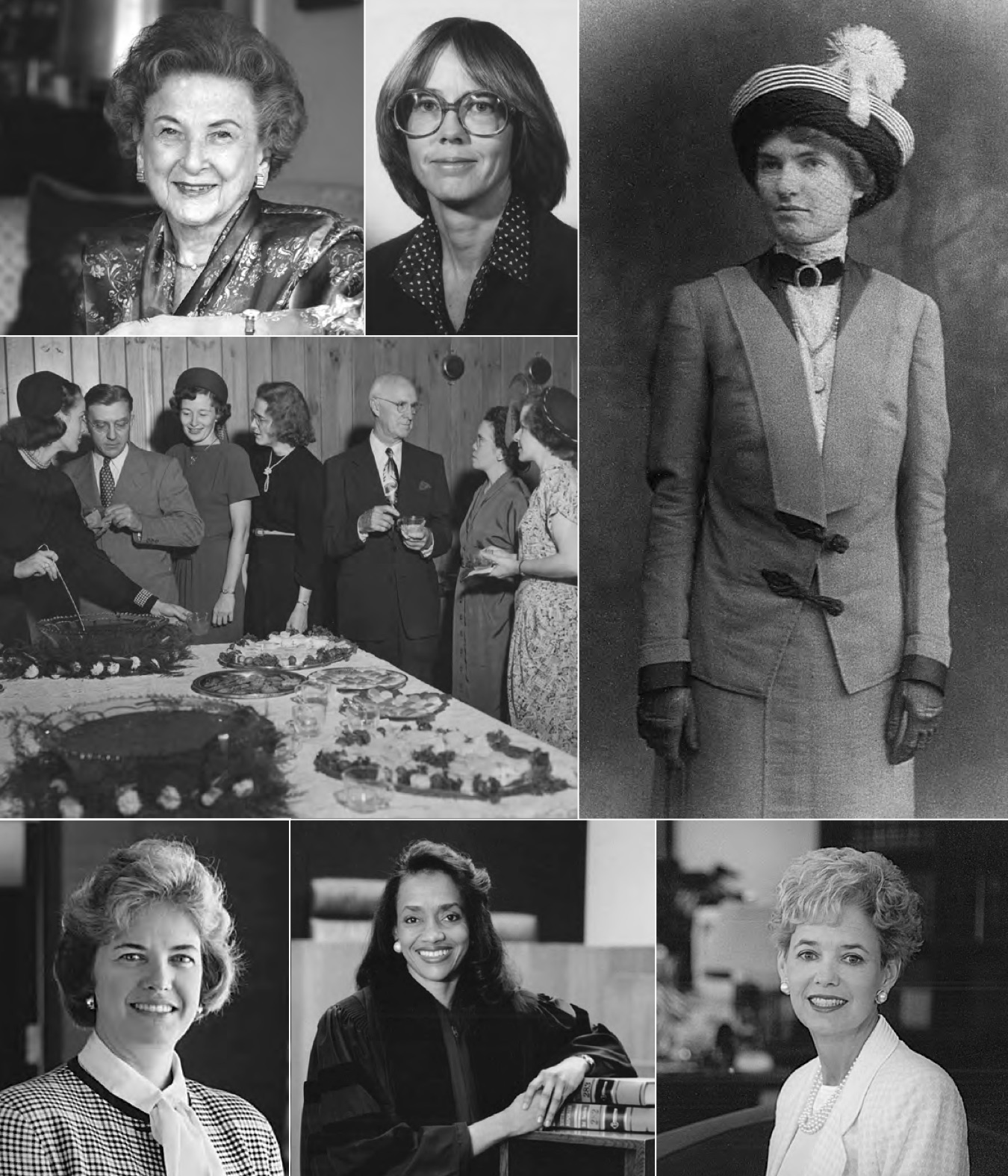

Emory Law is a great place to teach civil rights history, in part because Atlanta - the “city too busy to hate” - was so important during the civil rights movement.1 Some aspects of Emory Law’s history are very well documented. This is especially true of the experiences of Marvin Arrington 67L and Clarence Cooper 67L, who were among the first African American students to attend the law school’s day division, and of Emory’s effort to make law school more accessible to students of color by creating the Pre-Start program as an alternative to reliance on the LSAT.2 But there are surprising gaps, even in the history of racial integration and inclusion. Seminar member Kaylynn Webb 17L discovered that less is known about the very first African American student at Emory Law, Theodore E. Smith, who matriculated at the law school even before Arrington and Cooper. He entered in 1962, graduated in 1965, and went on to be Georgia’s first African American United States Assistant Attorney. Research by Jasmine Roper 18L revealed that the involvement of African American students in law school activities like moot court is difficult to track due to a lack of record keeping.

Class readings and activities were designed around student research interests. We held one class meeting at Emory’s Rose Library. Archivists made available Emory University records and talked with the class on the ways these sources could inform their work. Law Librarian Thomas Sneed 17B helped the class with secondary source research, and Vanessa King guided them through research in law school archives. We conducted an in-class oral history interview with Professor Kathleen Cleaver, the first African American female professor at the law school. These activities enabled students with no previous experience doing historical work to conduct their own research in primary sources. They came away with practical research skills relevant to law practice.

Webb’s paper shed new light on a well-known topic. Emory University brought suit in 1962 to challenge a state law denying tax-exempt status if a traditionally one-race school admitted students of a different race. The successful lawsuit opened the door to racial integration. Her paper showed that support for desegregation was relatively recent when that lawsuit was filed. Emory President Goodrich White objected to a federal report in 1947 calling for desegregation because he “believed that the traditions of the South should not be forcefully altered.” In 1951, the law school’s Law Day program featured a debate for and against desegregation. Ultimately, in the context of the civil rights movement and student activism on campus, the Board of Trustees voted to admit African American students as soon as the university could do so without jeopardizing its tax-exempt status. While the morality and justice of desegregation was at the forefront of deliberations, this action may also have aided the law school’s goal at the time to raise its profile and to be an elite national law school.

Other seminar papers illuminated the way that formal legal access to education cannot eliminate all barriers to inclusion. Sarah Tona 17L wrote of an undergraduate student with a neuromuscular disability in the early 1980s who had to crawl up flights of stairs on her hands and knees to register for student housing and to attend her classes. She would “put her head down to avoid the piercing stares of passersby, and arrived up to an hour early to ensure that she had enough time to take the trip.” With regulations already in place to implement a federal law requiring access to higher education for students with disabilities, this student’s story powerfully illustrates that the gap between law on the books and implementation can cause immeasurable pain.

Roper’s paper was motivated by a panelist at a recent Emory Black Law Students Association event who referred to herself as one of the “chosen two” in her class who participated on moot court. Roper found that four African American students participated in the “case club,” a precursor to moot court in 1969–70, but in later years their numbers remained small. Lacking records on moot court participation, Roper relied on oral history interviews with law school graduates. Her paper reveals persistent concern about diversity in the program, but also that important mentors have instead steered students toward participating in journals.

A history of Muslim students and Islamophobia at Emory, explored by Syed Hussain 17L, illustrates that the path of history does not inevitably lead toward increased tolerance. He wrote of a college freshman who had looked to Emory as a “haven of diversity,” before the campus climate became tense for Muslim students in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks. The atmosphere generated a need for community, which strengthened ties among Muslim students and led the university to be more attentive to the needs of this religious minority.

The research papers that required the most creativity explored the history of LGBTQ students. A 2005 study found that “a significant number” of LGBTQ students “reported going at least partially back into the closet upon entering law school.”3 There are records of organizations in the university’s archives, but the experience of students themselves is either blocked for reasons of privacy or unknown because they chose not to reveal it. This led Schladt to decide to write of her own story at Emory Law in an effort to create a record that had not existed. Articles about the LGBTQ experience in earlier years discussed difficult and disheartening experiences in Constitutional Law during the years that Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), which upheld the criminalization of gay sex, was the law. Schladt was surprised to find the same silence in the classroom when the marriage equality case, Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), was on the agenda. Still, her paper is ultimately hopeful, showing the way “strength will be found in coalition,” and the importance of reaching out to build “larger networks of belonging.”

Everett Arthur 17L’s history of trans and gender-non-conforming students creatively integrated the story of Scott Turner Schofield,4 Emory’s first openly transgender student, with narratives of North Carolina trans high school activists and the context of a broader national climate. Quoting Audre Lorde: “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive,”5 the paper emphasized that the most marginalized must be able to tell their own stories. Yet the paper concluded that, in a future that looks “precarious” and dangerous, defining one’s own story can require nothing less than bravery.

What began as a project to uncover a historical record ultimately fused with the creation of one, as Vanessa King invited the class to add their papers to the Emory Law archive. For my students, Emory’s history was not simply waiting to be uncovered. It was present in the classroom, to be revealed in my students’ own stories.

Mary L. Dudziak is a leading US legal historian and is president of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations.

2 William B. Turner published two important articles on integration at Emory and the development of the Pre-Start program: William B. Turner, “The Ultimate Victory of a Productive Life: Ben F. Johnson, Jr. and African Americans at Emory Law School, 1961 –72,” 58 J. of Legal Educ. 568 (2008); William B. Turner, “A Bulwark against Anarchy: Affirmative Action, Emory Law School, and Southern Self-Help,” 5 Hastings Race & Poverty L. J. 195 (2008).

3 Kelly Strader, Brietta R. Clark, Robin Ingli, Elizabeth Kransberger, Lawrence Levine, and William Perez, “An Assessment of the Law School Climate for GLBT Students,” 58 J. of Legal Education 214, 220 –21 (2008).

4 Scott Turner Schofield graduated from Emory in 2002 with a BA in Theater. He was the first openly transgender actor to appear on daytime television. www.scotttschofield.com/

5 Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982)

Email the Editor