Scholarships make careers possible

In 2016, college graduates who had student loans left school with an average debt of $37,000, a record high. But that figure pales in comparison to many law students’ six-figure obligation.

Law school is a substantial investment, and Emory Law’s administration works to lessen the financial burden. About 90 percent of students receive some financial assistance, and more than 50 percent of the school’s endowment earnings go to fund scholarships, fellowships, and awards. The school solicits scholarship endowments.

Julie Mayfield 96L received a Woodruff Fellowship, one of Emory’s most competitive and generous awards. It covers tuition and fees and includes a stipend. Mayfield says leaving law school minus loans undoubtedly influenced her career choices.

“Although I initially started at a large law firm, not having debt enabled me to take a 40 percent pay cut when I was ready to leave,” she says. “Indeed, every job I’ve moved to since leaving the firm has involved a pay cut to some degree - sometimes just a few thousand dollars and twice up to $30,000 - but I was able to make those moves to the jobs I wanted because I was debt free. The Woodruff enabled my passion to direct my career instead of debt.”

Mayfield is now co-director of MountainTrue, an environmental policy and watchdog organization based in Asheville, NC, where in 2015, she was elected to the City Council. She hadn’t decided on a specific practice area when she entered law school. “I had no inkling of going into environmental law when I started,” she says. “I didn’t know anything about it. My plan was to work internationally on human rights and conflict resolution, hence my first summer work at the Carter Center, my position on the Emory International Law Review, and taking every international law course offered. But I discovered environmental law during my second summer at Long, Aldridge & Norman and loved it. They offered me a position, and off I went in that direction, never to look back.”

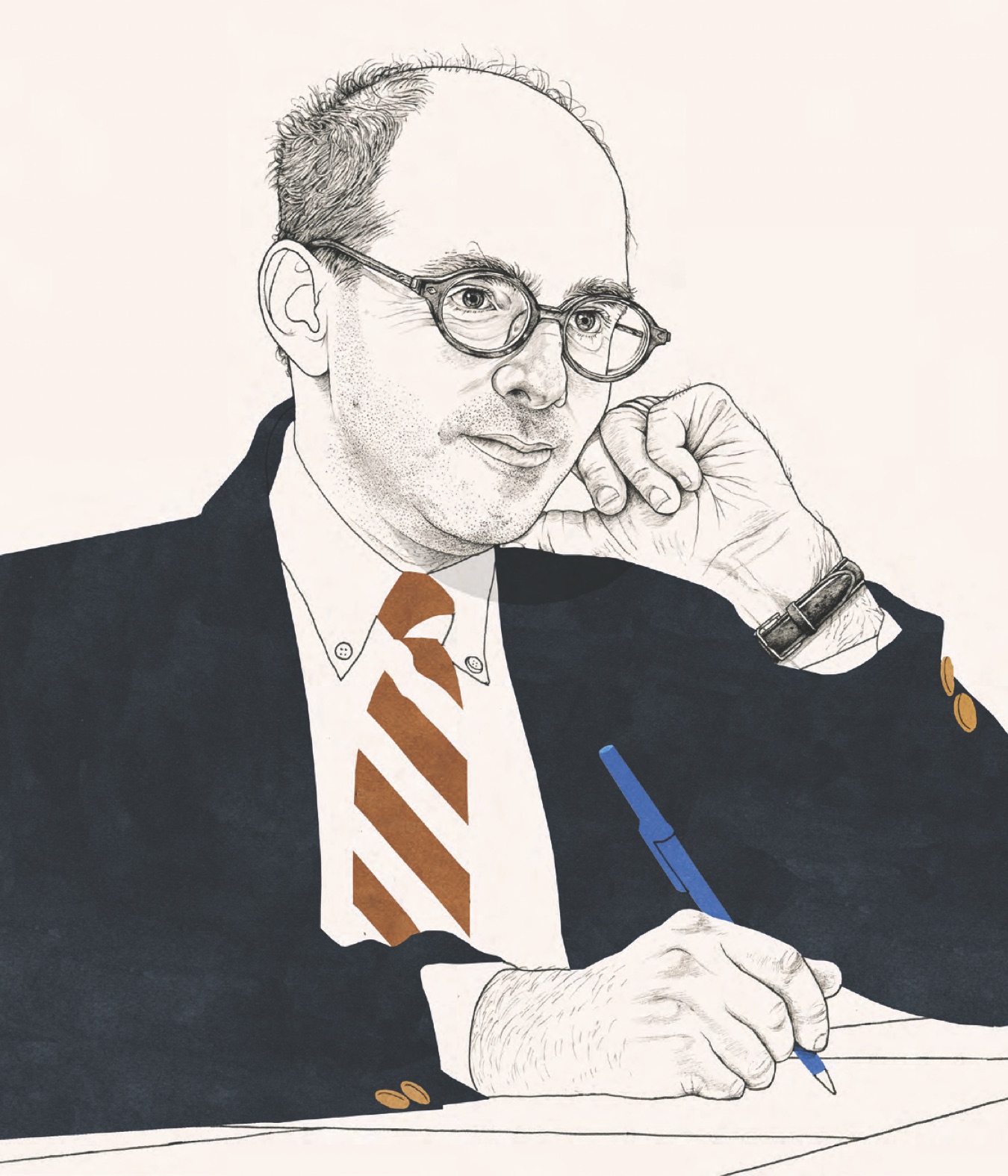

David Cohen 94L created an endowed scholarship.

“The scholarship was the school showing that they believed in my potential and were willing to share the investment I was making in myself,” he says.

So when he was considering a gift to Emory Law, Cohen decided a scholarship was the best way to repay Emory’s faith in him.

By any measure, Cohen is a remarkably successful lawyer - he is a litigator at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy who made partner in 2002. But he still remembers a day in the early ’90s when his first semester grades were posted, including a “D” in Civil Procedure. (It’s worth noting here, Cohen was later elected to membership in the Order of the Coif.) So when considering stipulations for a scholarship endowment, Cohen wasn’t stringent.

“I thought that admission and the aid department were in a much better position than I was to decide how this would best help a candidate pool and how it would help attract the people that they wanted,” Cohen says. “There’s enough pressure that students put on themselves with respect to class rank.”

Cohen serves on Emory Law’s Advisory Board. In addition to creating The David S. Cohen Scholarship (which has been awarded to two students thus far), he and his husband, Craig Benson, host an admitted students reception in Washington, DC. They decided several years ago to move it to their home in Dupont Circle.

The event affords a candid look at the students who will eventually become alumni.“I believe anybody who graduates with an Emory Law degree, people should take a very hard look at, because you’re talking about a quality, substantive, capable lawyer, whether you’re No. 1 in the class or in the bottom 10 percent of the class,” Cohen said.

At present, the Cohen scholarship disburses about $9,500 annually. The endowment will provide greater financial support as it grows, but Cohen likes the idea of a shared investment, reflecting the school’s faith in the student, and the student’s belief in the school.

“Until the scholarship gets to be a sufficient size, it’s not even funding a quarter of the tuition,” Cohen says. “But it gave me a vehicle to continue to make an investment in Emory and to pay them back for the help that they gave me, because I wouldn’t be here if not for them.”

“It stems from my own experience,” he said. “It was access to an education that, without somebody having come before me and put scholarship money in, I couldn’t have done it,” he says. “I feel like I should repay that generosity.”

Molly Parmer 12L says that without scholarships she would never have been able to go to school.

“Without a scholarship, both then and now, I would never have been able to go to school,” Parmer told an audience in 2012.

After graduating from Georgia Tech, she worked as a special education teacher. She viewed law school as an aspiration but wasn’t sure how she would pay for it.

When Emory Law offered a Woodruff Fellowship, “that phone call changed everything,” Parmer says.

As a student she spent six months with the Georgia Innocence Project, which works to exonerate wrongly convicted inmates. After graduating with honors, Parmer spent three years as an assistant public defender in DeKalb County Superior Court. In 2015, she moved to the Federal Defender Program of Georgia’s Northern District.

“Generous contributions have the potential to turn a girl with a homemade wardrobe and no cash for school field trips into a lawyer with a degree from a renowned institution,” she says. But they also provide diversity for the institution, she adds. “My perspective is different than that of many of my peers, as are my motivation and my goals.”