Nuremberg Tribunals prosecutor Ferencz encourages students to think along humanitarian lines

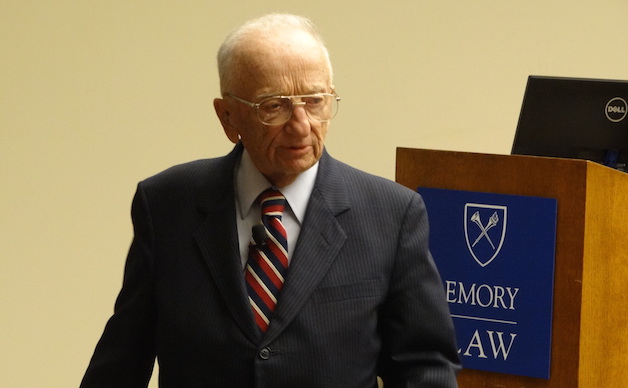

Ferencz, the last surviving chief prosecutor from the Nuremberg Tribunals, tells Emory Law students that they are "the hope of civilization." Photo courtesy of Andrea Videlefsky.

“War is hell, and law is better than war – no matter what.” Ben Ferencz, the last surviving chief prosecutor from the Nuremberg Tribunals, left no room for ambiguity when it comes to his position on war making. To a standing-room-only crowd at the law school on Monday, January 26, Ferencz recalled his experiences as an Army investigator and prosecutor of war crimes committed during World War II. In a lecture on international criminal justice, Ferencz recounted his part in what he called the biggest murder trial in history.

Born in what was then Transylvania, Ferencz and his family immigrated to the United States to escape pervasive persecution of Jews. Landing in crime-ridden Hell’s Kitchen, Ferencz would eventually attend Harvard Law School and serve in the U.S. Army. He was anticipating a position as a clerk. Instead, he was assigned to the artillery.

German and Japanese leaders had been warned that they would be held accountable for crimes committed during World War II, Ferencz said, and when it came time for those trials to take place, he helped develop a war crimes division. He gathered information and documents, feeding them back to prosecutors who built cases.

While his experiences in combat and as a member of the war crimes division earned Ferencz five battle stars, they also created in him an intense disdain for the inhumane treatment of people during wartime. “I have seen the horrors of war up close, “ he said. “And when it was over, I went home. I wanted no part of Germany.”

Sooner than he had hoped, though, Ferencz was called back to the place he’d so anxiously left. He returned to Berlin to help manage the subsequent Nuremberg Tribunals. Prosecutors tried doctors for performing medical experiments on concentration camp detainees. They tried lawyers who had perverted the law for political purposes and to get rid of their enemies. They tried industrialists who worked inmates to death and then sent them to crematoriums, sometimes turning their body fat into soap.

As Ferencz and his team of about 50 collected evidence, they found reports from the eastern front. These reports detailed murders by the Einsatzgruppen, cataloguing the methodical killing of Jews, Gypsies, and anyone else who could have posed a threat to the Reich. He fought for the ability to prosecute these crimes as well, and was named chief prosecutor for the Einsatzgruppen case at age 27. He recalled, “I tried 22 defendants for the murder of over one million people. But there were only 22 because we only had 22 seats in the dock. I picked them by their rank and their education. Several had PhDs and there were some who were studying for the ministry.”

Arguing on a plea of humanity to law, Ferencz opined that all people have the right to live in peace and dignity. After just two days, Ferencz rested his case. The accused were convicted, and 13 were sentenced to death.

It’s often said that the Nuremberg Tribunals were the birth of the international criminal justice movement. They certainly were the beginning of Ferencz’s quest for the establishment of the International Criminal Court – an entity that ultimately began operating in 2002.

However, there is still much work to be done in the arena of international criminal justice, including refining the definition of aggression, Ferencz suggested. “Criminal law is not to put people in jail. It’s to deter the crimes and create a more humane world. How do you do that? The first step is to stop glorifying war, and begin glorifying peace. You cannot kill an ideology with a gun. You have to have a better ideology.”

Substitute law for war, he said. And he wasn’t just speaking to the global law community. Ferencz issued a charge to each of Emory’s law students within his reach: “You are not here just to quibble. You are the hope of civilization. What’s so sacred about this crazy system that you can’t change it?”

Ferencz was a guest of Emory Law’s International Humanitarian Law Clinic, a unique program giving Emory Law students opportunities to work directly with organizations around the world to promote the law of armed conflict, enhance protections during wartime, and ensure accountability for war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity.